At Mozilla, we want WebAssembly to be as fast as it can be.

This started with its design, which gives it great throughput. Then we improved load times with a streaming baseline compiler. With this, we compile code faster than it comes over the network.

So what’s next?

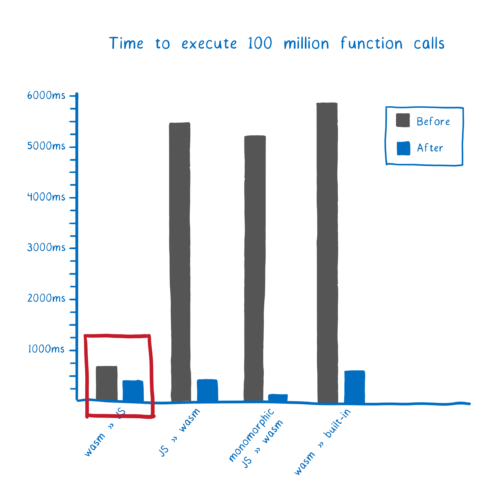

One of our big priorities is making it easy to combine JS and WebAssembly. But function calls between the two languages haven’t always been fast. In fact, they’ve had a reputation for being slow, as I talked about in my first series on WebAssembly.

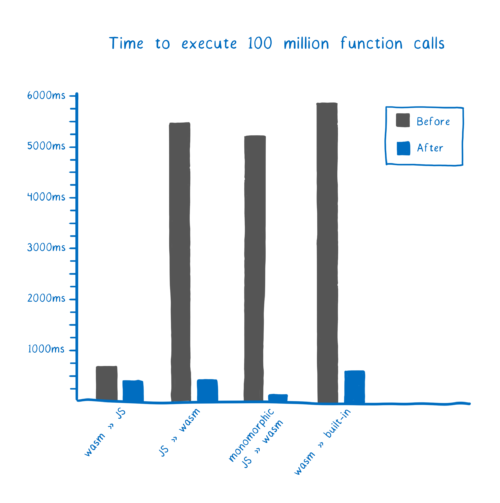

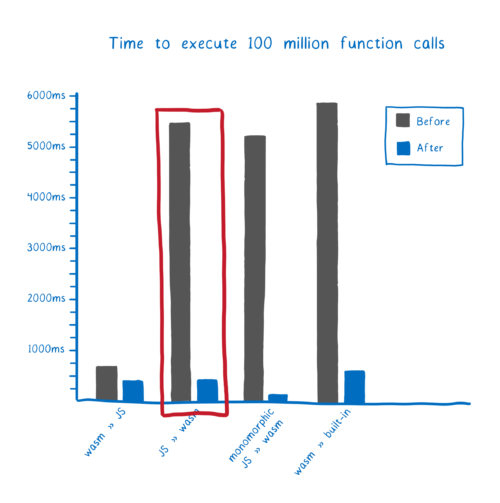

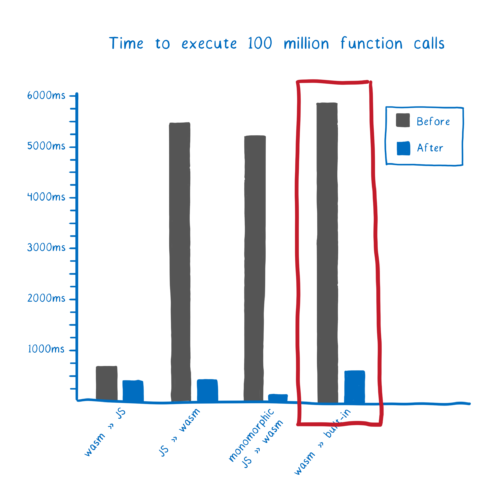

That’s changing, as you can see.

This means that in the latest version of Firefox Beta, calls between JS and WebAssembly are faster than non-inlined JS to JS function calls. Hooray! 🎉

So these calls are fast in Firefox now. But, as always, I don’t just want to tell you that these calls are fast. I want to explain how we made them fast. So let’s look at how we improved each of the different kinds of calls in Firefox (and by how much).

But first, let’s look at how engines do these calls in the first place. (And if you already know how the engine handles function calls, you can skip to the optimizations.)

How do function calls work?

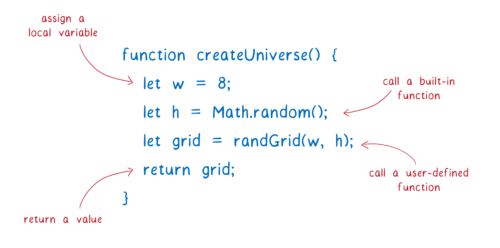

Functions are a big part of JavaScript code. A function can do lots of things, such as:

- assign variables which are scoped to the function (called local variables)

- use functions that are built-in to the browser, like

Math.random - call other functions you’ve defined in your code

- return a value

But how does this actually work? How does writing this function make the machine do what you actually want?

As I explained in my first WebAssembly article series, the languages that programmers use — like JavaScript — are very different than the language the computer understands. To run the code, the JavaScript we download in the .js file needs to be translated to the machine language that the machine understands.

Each browser has a built-in translator. This translator is sometimes called the JavaScript engine or JS runtime. However, these engines now handle WebAssembly too, so that terminology can be confusing. In this article, I’ll just call it the engine.

Each browser has its own engine:

- Chrome has V8

- Safari has JavaScriptCore (JSC)

- Edge has Chakra

- and in Firefox, we have SpiderMonkey

Even though each engine is different, many of the general ideas apply to all of them.

When the browser comes across some JavaScript code, it will fire up the engine to run that code. The engine needs to work its way through the code, going to all of the functions that need to be called until it gets to the end.

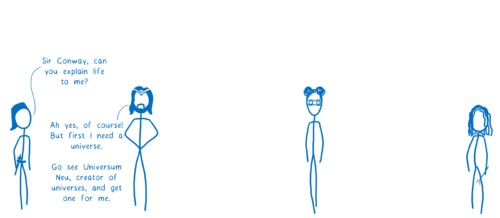

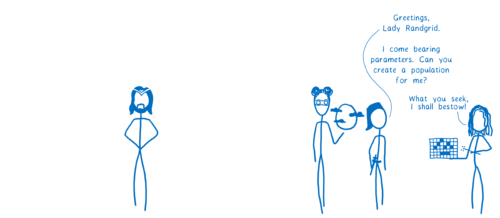

I think of this like a character going on a quest in a videogame.

Let’s say we want to play Conway’s Game of Life. The engine’s quest is to render the Game of Life board for us. But it turns out that it’s not so simple…

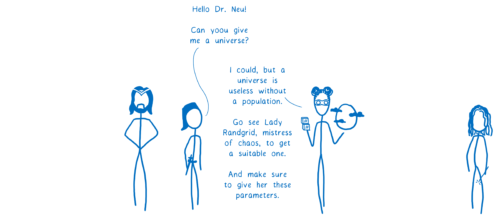

So the engine goes over to the next function. But the next function will send the engine on more quests by calling more functions.

The engine keeps having to go on these nested quests until it gets to a function that just gives it a result.

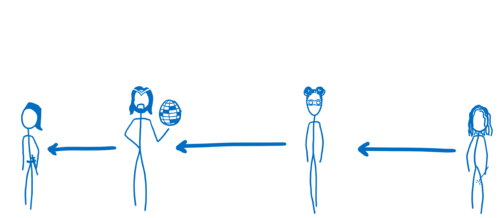

Then it can come back to each of the functions that it spoke to, in reverse order.

If the engine is going to do this correctly — if it’s going to give the right parameters to the right function and be able to make its way all the way back to the starting function — it needs to keep track of some information.

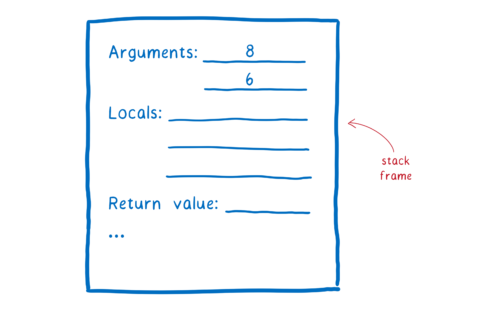

It does this using something called a stack frame (or a call frame). It’s basically like a sheet of paper that has the arguments to go into the function, says where the return value should go, and also keeps track of any of the local variables that the function creates.

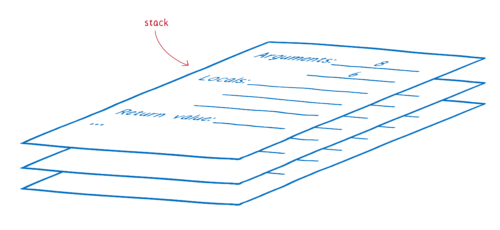

The way it keeps track of all of these slips of paper is by putting them in a stack. The slip of paper for the function that it is currently working with is on top. When it finishes that quest, it throws out the slip of paper. Because it’s a stack, there’s a slip of paper underneath (which has now been revealed by throwing away the old one). That’s where we need to return to.

This stack of frames is called the call stack.

The engine builds up this call stack as it goes. As functions are called, frames are added to the stack. As functions return, frames are popped off of the stack. This keeps happening until we get all the way back down and have popped everything out of the stack.

So that’s the basics of how function calls work. Now, let’s look at what made function calls between JavaScript and WebAssembly slow, and talk about how we’ve made this faster in Firefox.

How we made WebAssembly function calls fast

With recent work in Firefox Nightly, we’ve optimized calls in both directions — both JavaScript to WebAssembly and WebAssembly to JavaScript. We’ve also made calls from WebAssembly to built-ins faster.

All of the optimizations that we’ve done are about making the engine’s work easier. The improvements fall into two groups:

- Reducing bookkeeping —which means getting rid of unnecessary work to organize stack frames

- Cutting out intermediaries — which means taking the most direct path between functions

Let’s look at where each of these came into play.

Optimizing WebAssembly » JavaScript calls

When the engine is going through your code, it has to deal with functions that are speaking two different kinds of language—even if your code is all written in JavaScript.

Some of them—the ones that are running in the interpreter—have been turned into something called byte code. This is closer to machine code than JavaScript source code, but it isn’t quite machine code (and the interpreter does the work). This is pretty fast to run, but not as fast as it can possibly be.

Other functions — those which are being called a lot — are turned into machine code directly by the just-in-time compiler (JIT). When this happens, the code doesn’t run through the interpreter anymore.

So we have functions speaking two languages; byte code and machine code.

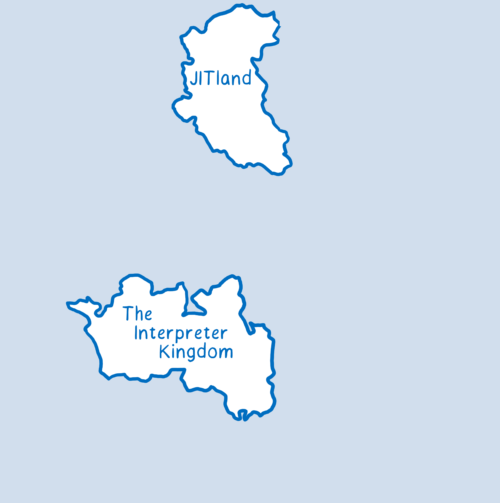

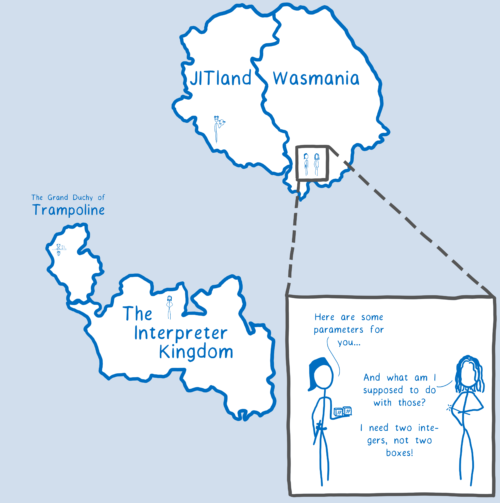

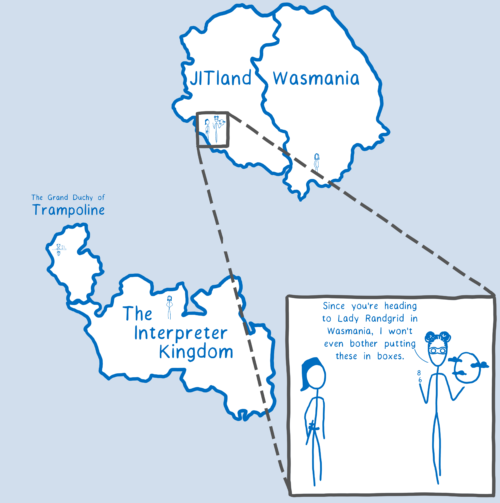

I think of these different functions which speak these different languages as being on different continents in our videogame.

The engine needs to be able to go back and forth between these continents. But when it does this jump between the different continents, it needs to have some information, like the place it left from on the other continent (which it will need to go back to). The engine also wants to separate the frames that it needs.

To organize its work, the engine gets a folder and puts the information it needs for its trip in one pocket — for example, where it entered the continent from.

It will use the other pocket to store the stack frames. That pocket will expand as the engine accrues more and more stack frames on this continent.

Sidenote: if you’re looking through the code in SpiderMonkey, these “folders” are called activations.

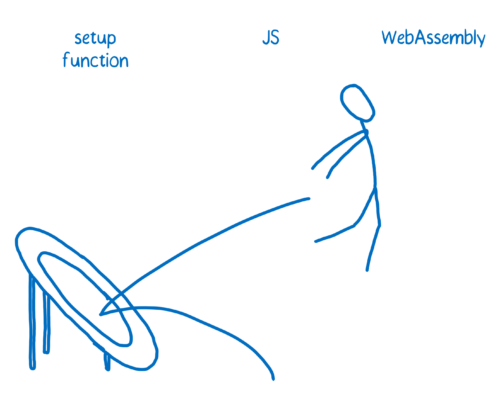

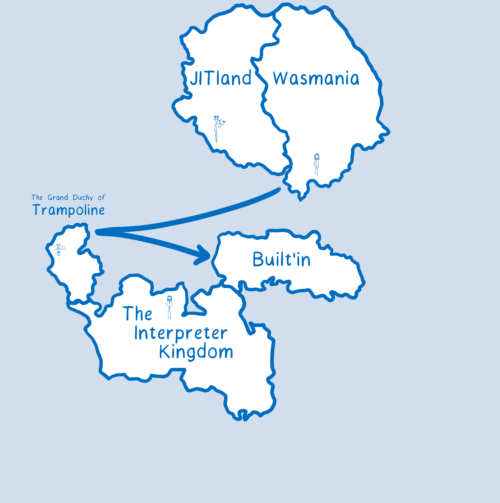

Each time it switches to a different continent, the engine will start a new folder. The only problem is that to start a folder, it has to go through C++. And going through C++ adds significant cost.

This is the trampolining that I talked about in my first series on WebAssembly.

Every time you have to use one of these trampolines, you lose time.

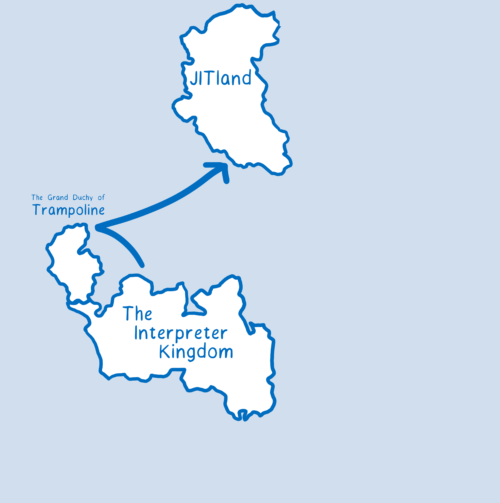

In our continent metaphor, it would be like having to do a mandatory layover on Trampoline Point for every single trip between two continents.

So how did this make things slower when working with WebAssembly?

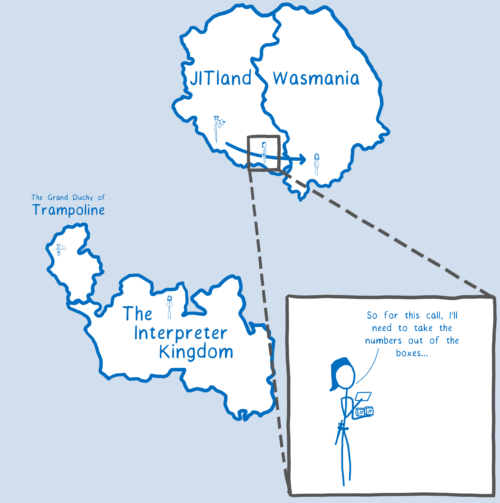

When we first added WebAssembly support, we had a different type of folder for it. So even though JIT-ed JavaScript code and WebAssembly code were both compiled and speaking machine language, we treated them as if they were speaking different languages. We were treating them as if they were on separate continents.

This was unnecessarily costly in two ways:

- it creates an unnecessary folder, with the setup and teardown costs that come from that

- it requires that trampolining through C++ (to create the folder and do other setup)

We fixed this by generalizing the code to use the same folder for both JIT-ed JavaScript and WebAssembly. It’s kind of like we pushed the two continents together, making it so you don’t need to leave the continent at all.

With this, calls from WebAssembly to JS were almost as fast as JS to JS calls.

We still had a little work to do to speed up calls going the other way, though.

Optimizing JavaScript » WebAssembly calls

Even in the case of JIT-ed JavaScript code, where JavaScript and WebAssembly are speaking the same language, they still use different customs.

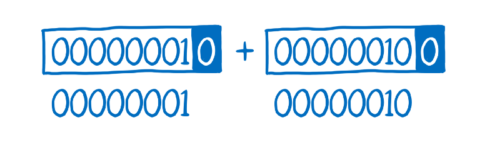

For example, to handle dynamic types, JavaScript uses something called boxing.

Because JavaScript doesn’t have explicit types, types need to be figured out at runtime. The engine keeps track of the types of values by attaching a tag to the value.

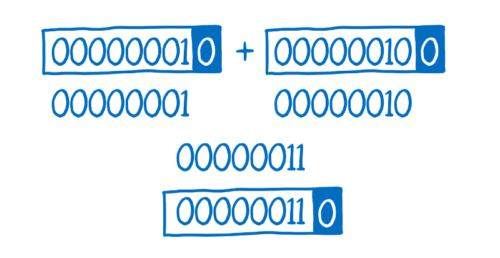

It’s as if the JS engine put a box around this value. The box contains that tag indicating what type this value is. For example, the zero at the end would mean integer.

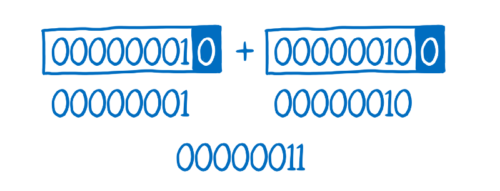

In order to compute the sum of these two integers, the system needs to remove that box. It removes the box for a and then removes the box for b.

Then it adds the unboxed values together.

Then it needs to add that box back around the results so that the system knows the result’s type.

This turns what you expect to be 1 operation into 4 operations… so in cases where you don’t need to box (like statically typed languages) you don’t want to add this overhead.

Sidenote: JavaScript JITs can avoid these extra boxing/unboxing operations in many cases, but in the general case, like function calls, JS needs to fall back to boxing.

This is why WebAssembly expects parameters to be unboxed, and why it doesn’t box its return values. WebAssembly is statically typed, so it doesn’t need to add this overhead. WebAssembly also expects values to be passed in at a certain place — in registers rather than the stack that JavaScript usually uses.

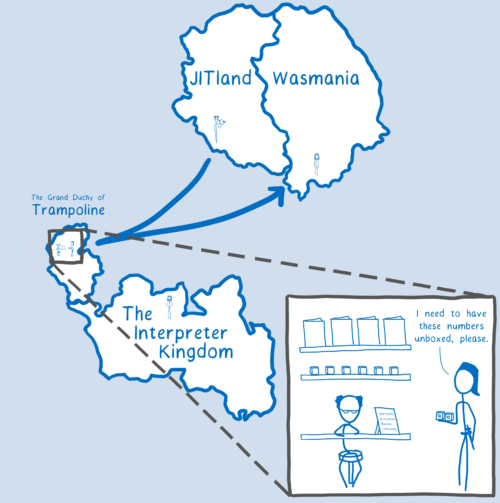

If the engine takes a parameter that it got from JavaScript, wrapped inside of a box, and gives it to a WebAssembly function, the WebAssembly function wouldn’t know how to use it.

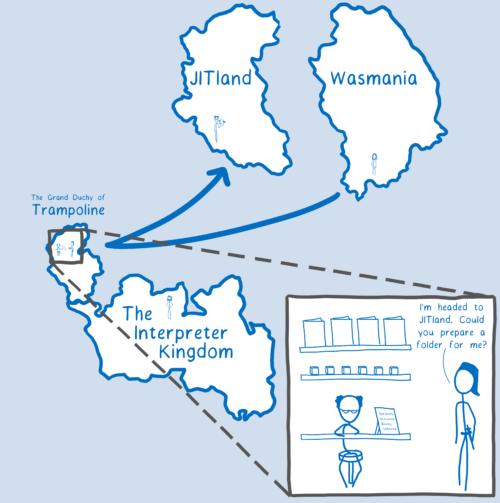

So, before it gives the parameters to the WebAssembly function, the engine needs to unbox the values and put them in registers.

To do this, it would go through C++ again. So even though we didn’t need to trampoline through C++ to set up the activation, we still needed to do it to prepare the values (when going from JS to WebAssembly).

Going to this intermediary is a huge cost, especially for something that’s not that complicated. So it would be better if we could cut the middleman out altogether.

That’s what we did. We took the code that C++ was running — the entry stub — and made it directly callable from JIT code. When the engine goes from JavaScript to WebAssembly, the entry stub un-boxes the values and places them in the right place. With this, we got rid of the C++ trampolining.

I think of this as a cheat sheet. The engine uses it so that it doesn’t have to go to the C++. Instead, it can unbox the values when it’s right there, going between the calling JavaScript function and the WebAssembly callee.

So that makes calls from JavaScript to WebAssembly fast.

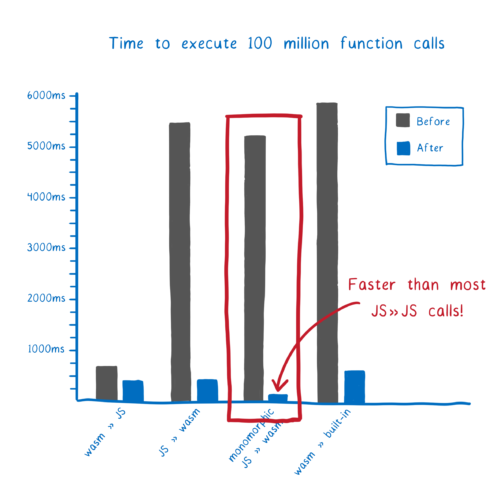

But in some cases, we can make it even faster. In fact, we can make these calls even faster than JavaScript » JavaScript calls in many cases.

Even faster JavaScript » WebAssembly: Monomorphic calls

When a JavaScript function calls another function, it doesn’t know what the other function expects. So it defaults to putting things in boxes.

But what about when the JS function knows that it is calling a particular function with the same types of arguments every single time? Then that calling function can know in advance how to package up the arguments in the way that the callee wants them.

This is an instance of the general JS JIT optimization known as “type specialization”. When a function is specialized, it knows exactly what the function it is calling expects. This means it can prepare the arguments exactly how that other function wants them… which means that the engine doesn’t need that cheat sheet and spend extra work on unboxing.

This kind of call — where you call the same function every time — is called a monomorphic call. In JavaScript, for a call to be monomorphic, you need to call the function with the exact same types of arguments each time. But because WebAssembly functions have explicit types, calling code doesn’t need to worry about whether the types are exactly the same — they will be coerced on the way in.

If you can write your code so that JavaScript is always passing the same types to the same WebAssembly exported function, then your calls are going to be very fast. In fact, these calls are faster than many JavaScript to JavaScript calls.

Future work

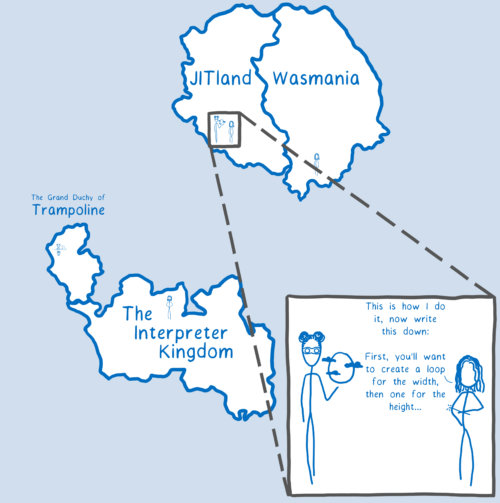

There’s only one case where an optimized call from JavaScript » WebAssembly is not faster than JavaScript » JavaScript. That is when JavaScript has in-lined a function.

The basic idea behind in-lining is that when you have a function that calls the same function over and over again, you can take an even bigger shortcut. Instead of having the engine go off to talk to that other function, the compiler can just copy that function into the calling function. This means that the engine doesn’t have to go anywhere — it can just stay in place and keep computing.

I think of this as the callee function teaching its skills to the calling function.

This is an optimization that JavaScript engines make when a function is being run a lot — when it’s “hot” — and when the function it’s calling is relatively small.

We can definitely add support for in-lining WebAssembly into JavaScript at some point in the future, and this is a reason why it’s nice to have both of these languages working in the same engine. This means that they can use the same JIT backend and the same compiler intermediate representation, so it’s possible for them to interoperate in a way that wouldn’t be possible if they were split across different engines.

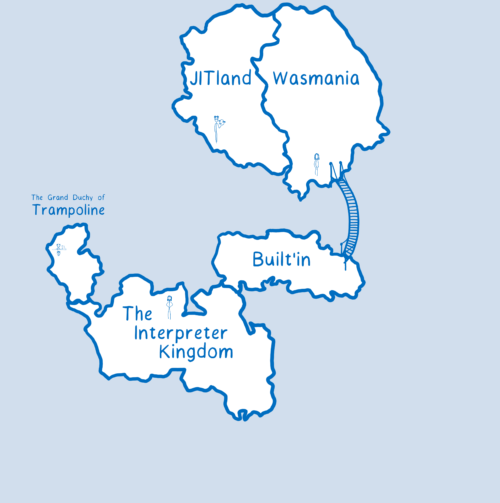

Optimizing WebAssembly » Built-in function calls

There was one more kind of call that was slower than it needed to be: when WebAssembly functions were calling built-ins.

Built-ins are functions that the browser gives you, like Math.random. It’s easy to forget that these are just functions that are called like any other function.

Sometimes the built-ins are implemented in JavaScript itself, in which case they are called self-hosted. This can make them faster because it means that you don’t have to go through C++: everything is just running in JavaScript. But some functions are just faster when they’re implemented in C++.

Different engines have made different decisions about which built-ins should be written in self-hosted JavaScript and which should be written in C++. And engines often use a mix of both for a single built-in.

In the case where a built-in is written in JavaScript, it will benefit from all of the optimizations that we have talked about above. But when that function is written in C++, we are back to having to trampoline.

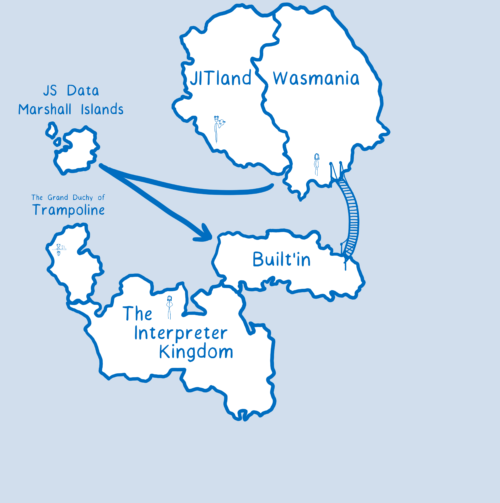

These functions are called a lot, so you do want calls to them to be optimized. To make it faster, we’ve added a fast path specific to built-ins. When you pass a built-in into WebAssembly, the engine sees that what you’ve passed it is one of the built-ins, at which point it knows how to take the fast-path. This means you don’t have to go through that trampoline that you would otherwise.

It’s kind of like we built a bridge over to the built-in continent. You can use that bridge if you’re going from WebAssembly to the built-in. (Sidenote: The JIT already did have optimizations for this case, even though it’s not shown in the drawing.)

With this, calls to these built-ins are much faster than they used to be.

Future work

Currently the only built-ins that we support this for are mostly limited to the math built-ins. That’s because WebAssembly currently only has support for integers and floats as value types.

That works well for the math functions because they work with numbers, but it doesn’t work out so well for other things like the DOM built-ins. So currently when you want to call one of those functions, you have to go through JavaScript. That’s what wasm-bindgen does for you.

But WebAssembly is getting more flexible types very soon. Experimental support for the current proposal is already landed in Firefox Nightly behind the pref javascript.options.wasm_gc. Once these types are in place, you will be able to call these other built-ins directly from WebAssembly without having to go through JS.

The infrastructure we’ve put in place to optimize the Math built-ins can be extended to work for these other built-ins, too. This will ensure many built-ins are as fast as they can be.

But there are still a couple of built-ins where you will need to go through JavaScript. For example, if those built-ins are called as if they were using new or if they’re using a getter or setter. These remaining built-ins will be addressed with the host-bindings proposal.

Conclusion

So that’s how we’ve made calls between JavaScript and WebAssembly fast in Firefox, and you can expect other browsers to do the same soon.

Thank you

Thank you to Benjamin Bouvier, Luke Wagner, and Till Schneidereit for their input and feedback.

About Lin Clark

Lin works in Advanced Development at Mozilla, with a focus on Rust and WebAssembly.

26 comments