ES6 In Depth is a series on new features being added to the JavaScript programming language in the 6th Edition of the ECMAScript standard, ES6 for short.

Welcome back to ES6 In Depth! I hope you had as much fun as I did during our summer break. But the life of a programmer cannot be all fireworks and lemonade. It’s time to pick up where we left off—and I’ve got the perfect topic to resume with.

Back in May, I wrote about generators, a new kind of function introduced in ES6. I called them the most magical feature in ES6. I talked about how they might be the future of asynchronous programming. And then I wrote this:

There is more to say about generators… But I think this post is long and bewildering enough for now. Like generators themselves, we should pause, and take up the rest another time.

Now is the time.

You can find part 1 of this article here. It’s probably best to read that before reading this. Go on, it’s fun. It’s… a little long and bewildering. But there’s a talking cat!

A quick revue

Last time, we focused on the basic behavior of generators. It’s a little strange, perhaps, but not hard to understand. A generator-function is a lot like a regular function. The main difference is that the body of a generator-function doesn’t run all at once. It runs a little bit at a time, pausing each time execution reaches a yield expression.

There’s a detailed explanation in part 1, but we never did a thorough worked example of how all the parts come together. Let’s do that now.

<pre>

function* someWords() {

yield "hello";

yield "world";

}

for (var word of someWords()) {

alert(word);

}

</pre>

This script is straightforward enough. But if you could observe everything that happens here, as though all the various bits of code were characters in a play, that would be a rather different script. It might go something like this:

SCENE - INTERIOR COMPUTER, DAY

FOR LOOP stands alone onstage, wearing a hard hat and

carrying a clipboard, all business.

FOR LOOP

(calling)

someWords()!

The GENERATOR appears: a tall, brass, clockwork gentleman.

It looks friendly enough, but it's still as a statue.

FOR LOOP

(clapping her hands smartly)

All right! Let's get some stuff done.

(to the generator)

.next()!

The GENERATOR springs to life.

GENERATOR

{value: "hello", done: false}

It freezes in a goofy pose.

FOR LOOP

alert!

Enter ALERT at a sprint, wide-eyed and breathless. We sense

he's always like that.

FOR LOOP

Tell the user "hello".

ALERT turns around and sprints offstage.

ALERT

(offstage, screaming)

Stop everything!

The web page at hacks.mozilla.org says,

"hello"!

A few seconds' pause, then ALERT races back on, crossing all

the way over to FOR LOOP and skidding to a halt.

ALERT

The user says OK.

FOR LOOP

(clapping her hands smartly)

All right! Let's get some stuff done.

(turning back to the GENERATOR)

.next()!

The GENERATOR again springs to life.

GENERATOR

{value: "world", done: false}

It freezes in a different goofy pose.

FOR LOOP

alert!

ALERT

(already running)

On it!

(offstage, screaming)

Stop everything!

The web page at hacks.mozilla.org says,

"world"!

Again, a pause, then ALERT trudges back onstage, suddenly

crestfallen.

ALERT

The user says OK again, but...

but please prevent this page from

creating additional dialogues.

He exits, pouting.

FOR LOOP

(clapping her hands smartly)

All right! Let's get some stuff done.

(turning back to the GENERATOR)

.next()!

The GENERATOR springs to life a third time.

GENERATOR

(with dignity)

{value: undefined, done: true}

Its head comes to rest on its chest and the lights go out of

its eyes. It will never move again.

FOR LOOP

Time for my lunch break.

She exits.

After a while, the GARBAGE COLLECTOR enters, picks up the

lifeless GENERATOR, and carries it offstage.

All right—it’s not exactly Hamlet. But you get the picture.

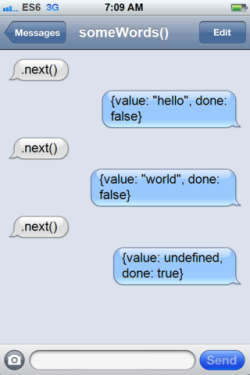

As you can see in the play, when a generator object first appears, it is paused. It wakes up and runs for a bit each time its .next() method is called.

The action is synchronous and single-threaded. Note that only one of these characters is actually doing anything at any given time. The characters never interrupt each other or talk over one another. They take turns speaking, and whoever’s talking can go on as long as they want. (Just like Shakespeare!)

And some version of this drama unfolds each time a generator is fed to a for–of loop. There is always this sequence of .next() method calls that do not appear anywhere in your code. Here I’ve put it all onstage, but for you and your programs, all this will happen behind the scenes, because generators and the for–of loop were designed to work together, via the iterator interface.

So to summarize everything up to this point:

- Generator objects are polite brass robots that yield values.

- Each robot’s programming consists of a single chunk of code: the body of the generator function that created it.

How to shut down a generator

Generators have several fiddly extra features that I didn’t cover in part 1:

generator.return()- the optional argument to

generator.next() generator.throw(error)yield*

I skipped them mainly because without understanding why those features exist, it’s hard to care about them, much less keep them all straight in your head. But as we think more about how our programs will use generators, we’ll see the reasons.

Here’s a pattern you’ve probably used at some point:

<pre>

function doThings() {

setup();

try {

// ... do some things ...

} finally {

cleanup();

}

}

doThings();

</pre>

The cleanup might involve closing connections or files, freeing system resources, or just updating the DOM to turn off an “in progress” spinner. We want this to happen whether our work finishes successfully or not, so it goes in a finally block.

How would this look in a generator?

<pre>

function* produceValues() {

setup();

try {

// ... yield some values ...

} finally {

cleanup();

}

}

for (var value of produceValues()) {

work(value);

}

</pre>

This looks all right. But there is a subtle issue here: the call work(value) isn’t inside the try block. If it throws an exception, what happens to our cleanup step?

Or suppose the for–of loop contains a break or return statement. What happens to the cleanup step then?

It executes anyway. ES6 has your back.

When we first discussed iterators and the for–of loop, we said the iterator interface contains an optional .return() method which the language automatically calls whenever iteration exits before the iterator says it’s done. Generators support this method. Calling myGenerator.return() causes the generator to run any finally blocks and then exit, just as if the current yield point had been mysteriously transformed into a return statement.

Note that the .return() is not called automatically by the language in all contexts, only in cases where the language uses the iteration protocol. So it is possible for a generator to be garbage collected without ever running its finally block.

How would this feature play out on stage? The generator is frozen in the middle of a task that requires some setup, like building a skyscraper. Suddenly someone throws an error! The for loop catches it and sets it aside. She tells the generator to .return(). The generator calmly dismantles all its scaffolding and shuts down. Then the for loop picks the error back up, and normal exception handling continues.

Generators in charge

So far, the conversations we’ve seen between a generator and its user have been pretty one-sided. To break with the theater analogy for a second:

The user is in charge. The generator does its work on demand. But this isn’t the only way to program with generators.

In part 1, I said that generators could be used for asynchronous programming. Things you currently do with asynchronous callbacks or promise chaining could be done with generators instead. You may have wondered how exactly that is supposed to work. Why is the ability to yield (which after all is a generator’s only special power) sufficient? After all, asynchronous code doesn’t just yield. It makes stuff happen. It calls for data from files and databases. It fires off requests to servers. And then it returns to the event loop to wait for those asynchronous processes to finish. How exactly will generators do this? And without callbacks, how does the generator receive data from those files and databases and servers when it comes in?

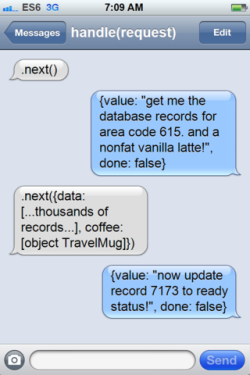

To start working toward the answer, consider what would happen if we just had a way for the .next() caller to pass a value back into the generator. With just this one change, we could have a whole new kind of conversation:

And a generator’s .next() method does in fact take an optional argument, and the clever bit is that the argument then appears to the generator as the value returned by the yield expression. That is, yield isn’t a statement like return; it’s an expression that has a value, once the generator resumes.

var results = yield getDataAndLatte(request.areaCode);

This does a lot of things for a single line of code:

- It calls

getDataAndLatte(). Let’s say that function returns the string"get me the database records for area code..."that we saw in the screenshot. - It pauses the generator, yielding the string value.

- At this point, any amount of time could pass.

- Eventually, someone calls

.next({data: ..., coffee: ...}). We store that object in the local variableresultsand continue on the next line of code.

To show that in context, here’s code for the entire conversation shown above:

<pre>

function* handle(request) {

var results = yield getDataAndLatte(request.areaCode);

results.coffee.drink();

var target = mostUrgentRecord(results.data);

yield updateStatus(target.id, "ready");

}

</pre>

Note how yield still just means exactly what it meant before: pause the generator and pass a value back to the caller. But how things have changed! This generator expects very specific supportive behavior from its caller. It seems to expect the caller to act like an administrative assistant.

Ordinary functions are not usually like that. They tend to exist to serve their caller’s needs. But generators are code you can have a conversation with, and that makes for a wider range of possible relationships between generators and their callers.

What might this administrative assistant generator-runner look like? It doesn’t have to be all that complicated. It might look like this.

<pre>

function runGeneratorOnce(g, result) {

var status = g.next(result);

if (status.done) {

return; // phew!

}

// The generator has asked us to fetch something and

// call it back when we're done.

doAsynchronousWorkIncludingEspressoMachineOperations(

status.value,

(error, nextResult) => runGeneratorOnce(g, nextResult));

}

</pre>

To get the ball rolling, we would have to create a generator and run it once, like this:

runGeneratorOnce(handle(request), undefined);

In May, I mentioned Q.async() as an example of a library that treats generators as asynchronous processes and automatically runs them as needed. runGeneratorOnce is that sort of thing. In practice, generator will not yield strings spelling out what they need the caller to do. They will probably yield Promise objects.

If you already understand promises, and now you understand generators, you might want to try modifying runGeneratorOnce to support promises. It’s a difficult exercise, but once you’re done, you’ll be able to write complex asynchronous algorithms using promises as straight-line code, not a .then() or a callback in sight.

How to blow up a generator

Did you notice how runGeneratorOnce handles errors? It ignores them!

Well, that’s not good. We would really like to report the error to the generator somehow. And generators support this too: you can call generator.throw(error) rather than generator.next(result). This causes the yield expression to throw. Like .return(), the generator will typically be killed, but if the current yield point is in a try block, then catch and finally blocks are honored, so the generator may recover.

Modifying runGeneratorOnce to make sure .throw() gets called appropriately is another great exercise. Keep in mind that exceptions thrown inside generators are always propagated to the caller. So generator.throw(error) will throw error right back at you unless the generator catches it!

This completes the set of possibilities when a generator reaches a yield expression and pauses:

- Someone may call

generator.next(value). In this case, the generator resumes execution right where it left off. - Someone may call

generator.return(), optionally passing a value. In this case, the generator does not resume whatever it was doing. It executesfinallyblocks only. - Someone may call

generator.throw(error). The generator behaves as if theyieldexpression were a call to a function that threwerror. - Or, maybe nobody will do any of those things. The generator might stay frozen forever. (Yes, it is possible for a generator to enter a

tryblock and simply never execute thefinallyblock. A generator can even be reclaimed by the garbage collector while it’s in this state.)

This is not much more complicated than a plain old function call. Only .return() is really a new possibility.

In fact, yield has a lot in common with function calls. When you call a function, you’re temporarily paused, right? The function you called is in control. It might return. It might throw. Or it might just loop forever.

Generators working together

Let me show off one more feature. Suppose we write a simple generator-function to concatenate two iterable objects:

<pre>

function* concat(iter1, iter2) {

for (var value of iter1) {

yield value;

}

for (var value of iter2) {

yield value;

}

}

</pre>

ES6 provides a shorthand for this:

<pre>

function* concat(iter1, iter2) {

yield* iter1;

yield* iter2;

}

A plain yield expression yields a single value; a yield* expression consumes an entire iterator and yields all values.

The same syntax also solves another funny problem: the problem of how to call a generator from within a generator. In ordinary functions, we can scoop up a bunch of code from one function and refactor it into a separate function, without changing behavior. Obviously we’ll want to refactor generators too. But we’ll need a way to call the factored-out subroutine and make sure that every value we were yielding before is still yielded, even though it’s a subroutine that’s producing those values now. yield* is the way to do that.

<pre>

function* factoredOutChunkOfCode() { ... }

function* refactoredFunction() {

...

yield* factoredOutChunkOfCode();

...

}

</pre>

Think of one brass robot delegating subtasks to another. You can see how important this idea is for writing large generator-based projects and keeping the code clean and organized, just as functions are crucial for organizing synchronous code.

Exeunt

Well, that’s it for generators! I hope you enjoyed that as much as I did, too. It’s good to be back.

Next week, we’ll talk about yet another mind-blowing feature that’s totally new in ES6, a new kind of object so subtle, so tricky, that you may end up using one without even knowing it’s there. Please join us next week for a look at ES6 proxies in depth.

8 comments