In this article, we’ll walk through the design and implementation of the prefers-contrast media query in Firefox. We’ll start by defining high contrast mode, then we’ll cover the importance of prefers-contrast. Finally, we’ll walk through the media query implementation in Firefox. By the end, you’ll have a greater understanding of how media queries work in Firefox, and why the prefers-contrast query is important and exciting.

When we talk about the contrast of a page we’re assessing how the web author’s color choices impact readability. For visitors with low vision web pages with low or insufficient contrast can be hard to use. The lack of distinction between text and its background can cause them to “bleed” together.

The What of prefers-contrast

Though the WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) set standards for contrast that authors should abide by, not all sites do. To keep the web accessible, many browsers and OSes offer high-contrast settings to change how web pages and content looks. When these settings are enabled we say that a website visitor has high contrast mode enabled.

High contrast mode increases the contrast of the screen so that users with low vision have an easier time getting around. Depending on what operating system is being used, high contrast mode can make a wide variety of changes. It can reduce the visual complexity of the screen, force high contrast colors between text and backgrounds, apply filters to the screen, and more. Doing this all automatically and in a way that works for every application and website is hard.

For example, how should high contrast mode handle images? Photos taken in high or low light may lack contrast, and their subjects may be hard to distinguish. What about text that is set on top of images? If the image isn’t a single color, some parts may have high contrast, but others may not. At the moment, Firefox deals with text on images by drawing a backplate on the text. All this is great, but it’s still not quite ideal. Ideally, webpages could detect when high contrast mode is enabled and then make themselves more accessible. To do that we need to know how different operating systems implement high contrast mode.

OS-level high-contrast settings

Most operating systems offer high-contrast settings. On macOS, users can indicate that they’d prefer high contrast in System Preferences → Accessibility → Display. To honor this preference, macOS applies a high contrast filter to the screen. However, it won’t do anything to inform applications that high contrast is enabled or adjust the layout of the screen. This makes it hard for apps running on macOS to adjust themselves for high-contrast mode users. Furthermore, it means that users are completely dependent on the operating system to make the right modifications.

Windows takes a very different approach. When high contrast mode is enabled, Windows exposes this information to applications. Rather than apply a filter to the screen, it forces applications to use certain high contrast (or user-defined) colors. Unlike macOS, Windows also tells applications when high-contrast settings are enabled. In this way, applications can adjust themselves to be more high-contrast friendly.

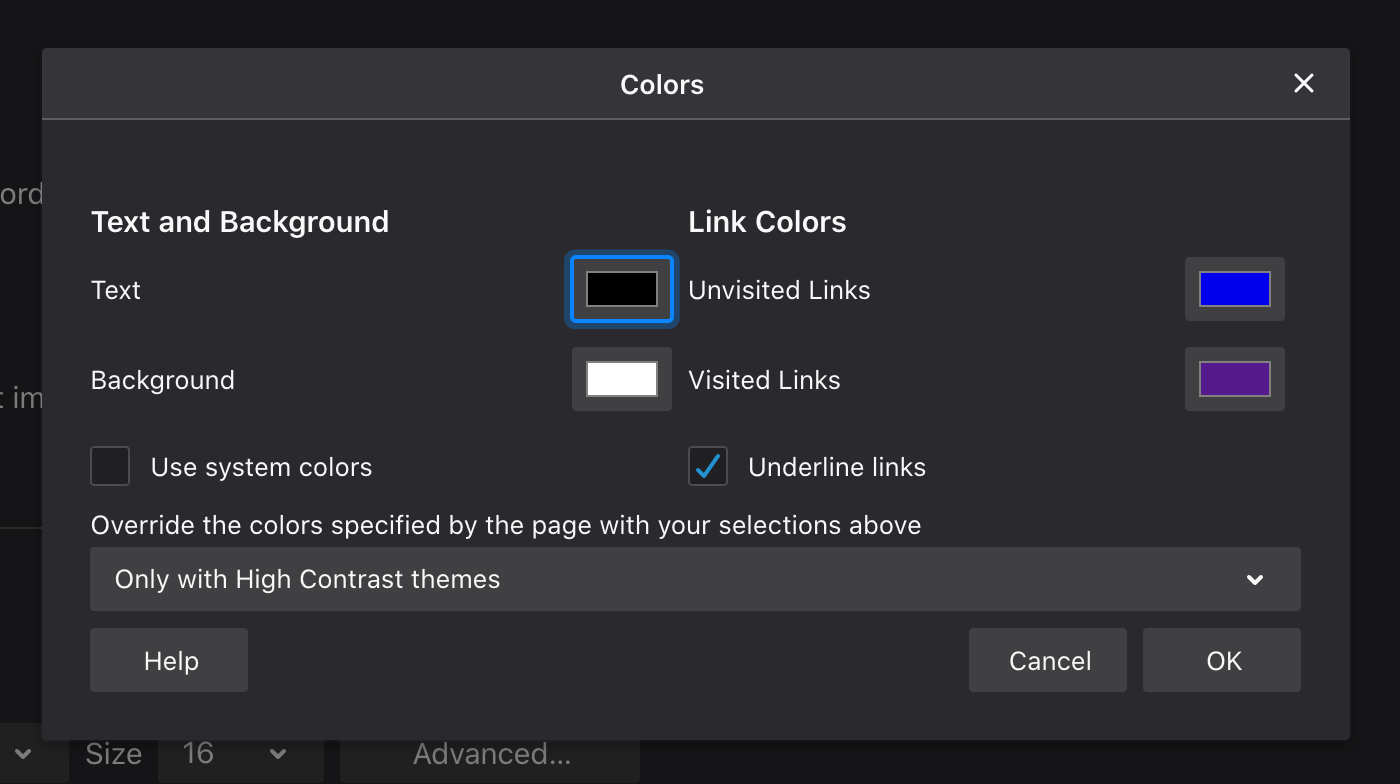

Similarly, Firefox lets users customize high contrast colors or apply different colors to web content. This option can be enabled via the colors option under “Language and Appearance” in Firefox’s “Preferences” settings on all operating systems. When we talk about colors set by the user instead of by the page or application, we describe them as forced.

Forced colors in Firefox

As we can see, different operating systems handle high-contrast settings in different ways. This impacts how prefers-contrast works on these platforms. On Windows, because Firefox is told when a high-contrast theme is in use, prefers-contrast can detect both high contrast from Windows and forced colors from within Firefox. On macOS, because Firefox isn’t told when a high-contrast theme is in use, prefers-contrast can only detect when colors are being forced from within the browser.

Want to see what something with forced colors looks like? Here is the Google homepage on Firefox with the default Windows high-contrast theme enabled:

Notice how Firefox overrides the background colors (forced) to black and overrides outlines to yellow.

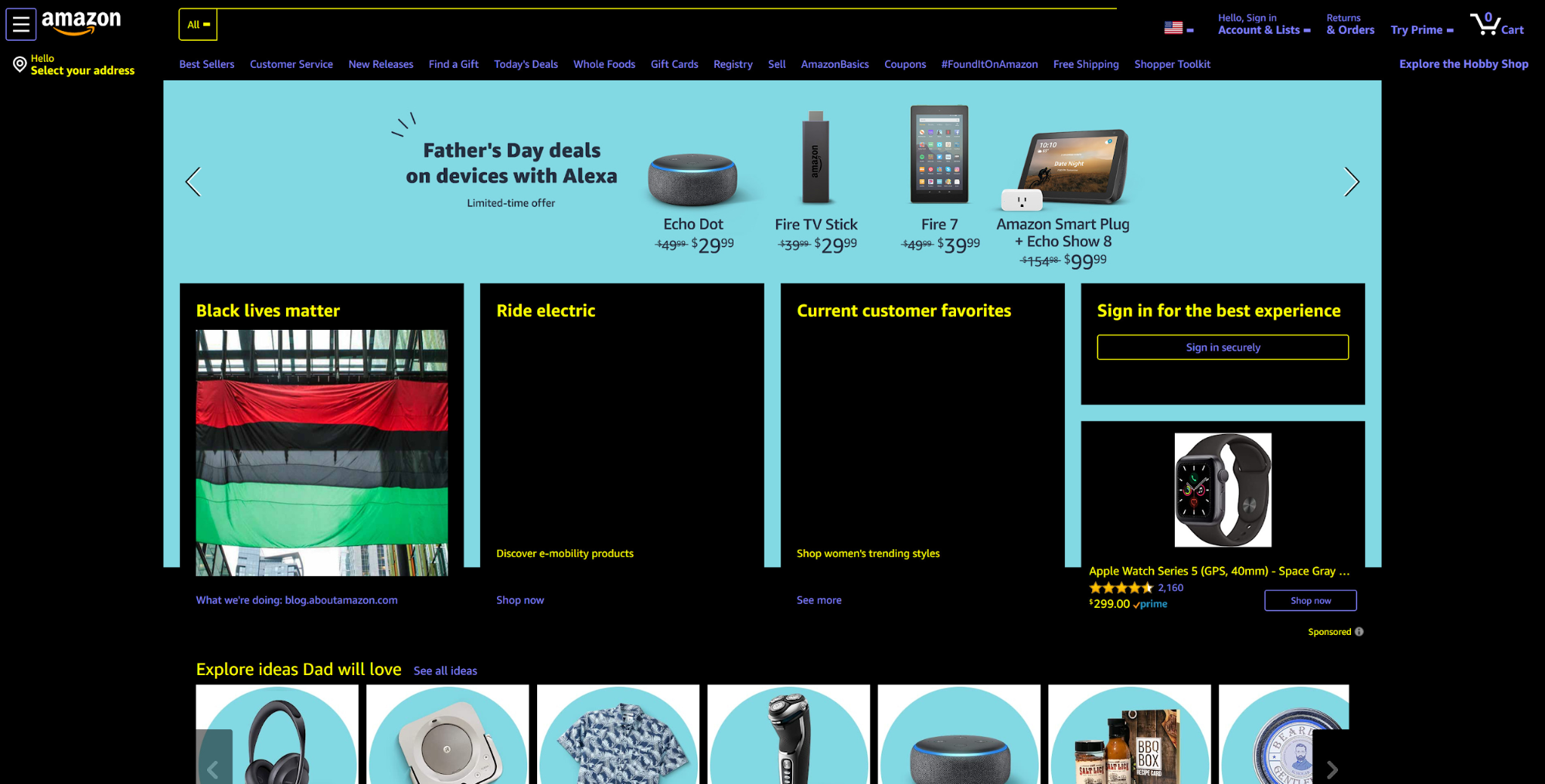

Some things are left to be desired by this forced colors approach. On the Google homepage above, you’ll notice that the profile image no longer appears next to the sign-in button. Here’s the Amazon homepage, also in Firefox, with the same Windows high-contrast theme enabled:

The images under “Ride electric” and “Current customer favorites” have disappeared, and the text in the “Father’s Day deals” section has not increased in contrast.

The Why of prefers-contrast

We can’t fault Google and Amazon for the missing images and other issues in the appearance of these high-contrast homepages. Without the prefers-contrast media query, there is no standardized way to detect a visitor’s contrast preferences. Even if Google and Amazon wanted to change their webpages to make them more accessible for different contrast preferences, they couldn’t. They have no way of knowing when a user has high-contrast mode enabled, even though the browser can tell.

That’s why prefers-contrast is so important. The prefers-contrast media query allows website authors to determine a visitor’s contrast preferences and update the website accordingly. Using prefers-contrast, a website author can differentiate between low and high contrast and detect when colors are being forced like this:

@media (prefers-contrast: forced) {

/* some awesome, accessible, high contrast css */

}

This is great because well-informed website designers are much better at making their webpages accessible than automatic high contrast settings.

The How of prefers-contrast

This section covers how something like prefers-contrast actually gets implemented in Firefox. It’s an interesting dive into the internals of a browser, but if you’re just interested in the what and why of perfers-contrast then you’re welcome to move on to the conclusion.

Parsing

We’ll start our media query implementation journey with parsing. Parsing handles turning CSS and HTML into an internal representation that the browser understands. Firefox uses a browser engine called Servo to handle this. Luckily for us, Servo makes things pretty straightforward. To hook up parsing for our media query, we’ll head over to media_features.rs in the Servo codebase and we’ll add an enum to represent our media query.

/// Possible values for prefers-contrast media query.

/// https://drafts.csswg.org/mediaqueries-5/#prefers-contrast

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug, FromPrimitive, PartialEq, Parse, ToCss)]

#[repr(u8)]

#[allow(missing_docs)]

enum PrefersContrast {

High,

Low,

NoPreference,

Forced,

}

Because we use #[derive(Parse)], Stylo will take care of generating the parsing code for us using the name of our enum and its options. It is seriously that easy. :-)

Evaluating the media query

Now that we’ve got our parsing logic hooked up, we’ll add some logic for evaluating our media query. If prefers-contrast only exposed low, no-preference, and high, then this would be as simple as creating some function that returns an instance of our enum above.

That said, the addition of a forced option adds some interesting gotchas to our media query. It’s not possible to simultaneously prefer low and high-contrast. However, it’s quite common for website visitors to prefer high contrast and have forced colors. Like we discussed earlier if a visitor is on Windows enabling high contrast also forces colors on webpages. Because enums can only be in one of their states at a time (i.e., the prefers-contrast enum can’t be high-contrast and fixed simultaneously) we’ll need to make some modifications to a single function design.

To properly represent prefers-contrast, we’ll split our logic in half. The first half will determine if colors are being forced and the second will determine the website visitor’s contrast preference. We can represent the presence or absence of forced colors with a boolean, but we’ll need a new enum for contrast preference. Let’s go ahead and add that to media_features.rs:

/// Represents the parts of prefers-contrast that explicitly deal with

/// contrast. Used in combination with information about rather or not

/// forced colors are active this allows for evaluation of the

/// prefers-contrast media query.

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug, FromPrimitive, PartialEq)]

#[repr(u8)]

pub enum ContrastPref {

/// High contrast is preferred. Corresponds to an accessibility theme

/// being enabled or firefox forcing high contrast colors.

High,

/// Low contrast is prefered. Corresponds to the

/// browser.display.prefers_low_contrast pref being true.

Low,

/// The default value if neither high nor low contrast is enabled.

NoPreference,

}

Voila! We have parsing and enums to represent the possible states of the prefers-contrast media query and a website visitor’s contrast preference done.

Adding functions in C++ and Rust

Now we add some logic to make prefers-contrast tick. We’ll do that in two steps. First, we’ll add a C++ function to determine contrast preferences, and then we’ll add a Rust function to call it and evaluate the media query.

Our C++ function will live in Gecko, Firefox’s layout engine. Information about high contrast settings is also collected in Gecko. This is quite handy for us. We’d like our C++ function to return our ContrastPref enum from earlier. Let’s start by generating bindings from Rust to C++ for that.

Starting in ServoBindings.toml we’ll add a mapping from our Stylo type to a Gecko type:

cbindgen-types = [

# ...

{ gecko = "StyleContrastPref", servo = "gecko::media_features::ContrastPref" },

# ...

]

Then, we’ll add a similar thing to Servo’s cbindgen.toml:

include = [

# ...

"ContrastPref",

# ...

]

And with that, we’ve done it! cbindgen will generate the bindings so we have an enum to use and return from C++ code.

We’ve written a C++ function that’s relatively straightforward. We’ll move over to nsMediaFeatures.cpp and add it. If the browser is resisting fingerprinting, we’ll return no-preference. Otherwise, we’ll return high- or no-preference based on whether or not we’ve enabled high contrast mode (UseAccessibilityTheme).

StyleContrastPref Gecko_MediaFeatures_PrefersContrast(const Document* aDocument, const bool aForcedColors) {

if (nsContentUtils::ShouldResistFingerprinting(aDocument)) {

return StyleContrastPref::NoPreference;

}

// Neither Linux, Windows, nor Mac has a way to indicate that low

// contrast is preferred so the presence of an accessibility theme

// implies that high contrast is preferred.

//

// Note that MacOS does not expose whether or not high contrast is

// enabled so for MacOS users this will always evaluate to

// false. For more information and discussion see:

// https://github.com/w3c/csswg-drafts/issues/3856#issuecomment-642313572

// https://github.com/w3c/csswg-drafts/issues/2943

if (!!LookAndFeel::GetInt(LookAndFeel::IntID::UseAccessibilityTheme, 0)) {

return StyleContrastPref::High;

}

return StyleContrastPref::NoPreference;

}

Aside: This implementation doesn’t have a way to detect a preference for low contrast. As we discussed earlier neither Windows, macOS, nor Linux has a standard way to indicate that low contrast is preferred. Thus, for our initial implementation, we opted to keep things simple and make it impossible to toggle. That’s not to say that there isn’t room for improvement here. There are various less standard ways for users to indicate that they prefer low contrast — like forcing low contrast colors on Windows, Linux, or in Firefox.

Determining contrast preferences in Firefox

Finally, we’ll add the function definition to GeckoBindings.h so that our Rust code can call it.

mozilla::StyleContrastPref Gecko_MediaFeatures_PrefersContrast(

const mozilla::dom::Document*, const bool aForcedColors);

Now that parsing, logic, and C++ bindings are set up, we’re ready to add our Rust function for evaluating the media query. Moving back over to media_features.rs, we’ll go ahead and add a function to do that.

Our function takes a device with information about where the media query is being evaluated. It includes an optional query value, representing the value that the media query is being evaluated against. The query value is optional because sometimes the media query can be evaluated without a query. In this case, we evaluate the truthiness of the contrast-preference that we normally would compare to the query. This is called evaluating the media query in the “boolean context”. If the contrast preference is anything other than no-preference, we go ahead and apply the CSS inside of the media query.

Contrast preference examples

That’s a lot of information, so here are some examples:

@media (prefers-contrast: high) { } /* query_value: Some(high) */

@media (prefers-contrast: low) { } /* query_value: Some(low) */

@media (prefers-contrast) { } /* query_value: None | "eval in boolean context" */

In the boolean context (the third example above) we first determine the actual contrast preference. Then, if it’s not no-preference the media query will evaluate to true and apply the CSS inside. On the other hand, if it is no-preference, the media query evaluates to false and we don’t apply the CSS.

With that in mind, let’s put together the logic for our media query!

fn eval_prefers_contrast(device: &Device, query_value: Option) -> bool {

let forced_colors = !device.use_document_colors();

let contrast_pref =

unsafe { bindings::Gecko_MediaFeatures_PrefersContrast(device.document(), forced_colors) };

if let Some(query_value) = query_value {

match query_value {

PrefersContrast::Forced => forced_colors,

PrefersContrast::High => contrast_pref == ContrastPref::High,

PrefersContrast::Low => contrast_pref == ContrastPref::Low,

PrefersContrast::NoPreference => contrast_pref == ContrastPref::NoPreference,

}

} else {

// Only prefers-contrast: no-preference evaluates to false.

forced_colors || (contrast_pref != ContrastPref::NoPreference)

}

}

The last step is to register our media query with Firefox. Still in media_features.rs, we’ll let Stylo know we’re done. Then we can add our function and enum to the media features list:

pub static MEDIA_FEATURES: [MediaFeatureDescription; 54] = [

// ...

feature!(

atom!("prefers-contrast"),

AllowsRanges::No,

keyword_evaluator!(eval_prefers_contrast, PrefersContrast),

// Note: by default this is only enabled in browser chrome and

// ua. It can be enabled on the web via the

// layout.css.prefers-contrast.enabled preference. See

// disabled_by_pref in media_feature_expression.rs for how that

// is done.

ParsingRequirements::empty(),

),

// ...

];

In conclusion

And with that, we’ve finished! With some care, we’ve walked through a near-complete implementation of prefers-contrast in Firefox. Triggered updates and tests are not covered, but are relatively small details. If you’d like to see all of the code and tests for prefers-contrast take a look at the Phabricator patch here.

prefers-contrast is a powerful and important media query that makes it easier for web authors to create accessible web pages. Using prefers-contrast websites can adjust to high and forced contrast preferences in ways that they were entirely unable to before. To get prefers-contrast, grab a copy of Firefox Nightly and set layout.css.prefers-contrast.enabled to true in about:config. Now, go forth and build a more accessible web! 🎉

Mozilla works to make the internet a global public resource that is open and accessible to all. The prefers-contrast media query, and other work by our accessibility team, ensures we uphold that commitment to our low-vision users and other users with disabilities. If you’re interested in learning more about Mozilla’s accessibility work you can check out the accessibility blog or the accessibility wiki page.

About Zeke Medley

Zeke is an intern on the layout team. He studies Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences at UC Berkeley and likes to play SimCity in his free time.

5 comments