This post was written in collaboration with the Rust Team (the “we” in this article). You can also read their announcement on the Rust blog.

Starting today, the Rust 2018 edition is in its first release. With this edition, we’ve focused on productivity… on making Rust developers as productive as they can be.

But beyond that, it can be hard to explain exactly what Rust 2018 is.

Some people think of it as a new version of the language, which it is… kind of, but not really. I say “not really” because if this is a new version, it doesn’t work like versioning does in other languages.

In most other languages, when a new version of the language comes out, any new features are added to that new version. The previous version doesn’t get new features.

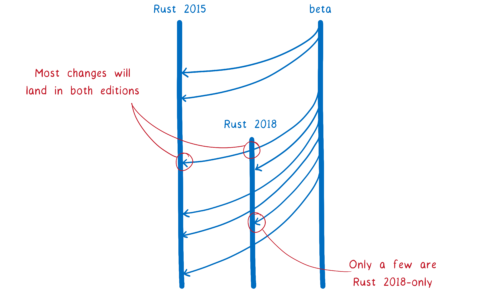

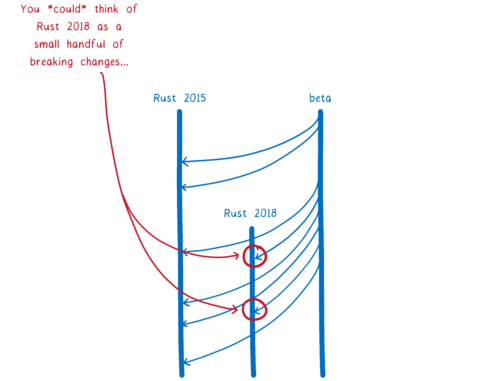

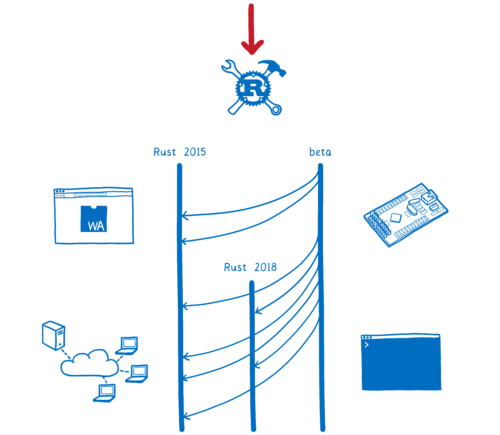

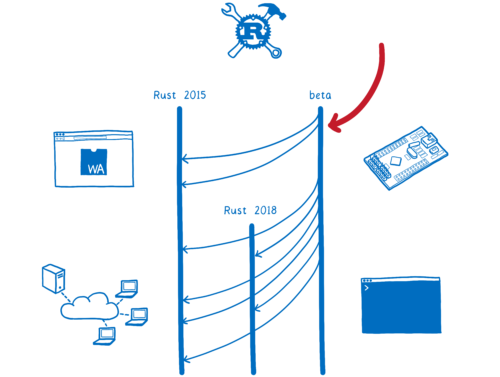

Rust editions are different. This is because of the way the language is evolving. Almost all of the new features are 100% compatible with Rust as it is. They don’t require any breaking changes. That means there’s no reason to limit them to Rust 2018 code. New versions of the compiler will continue to support “Rust 2015 mode”, which is what you get by default.

But sometimes to advance the language, you need to add things like new syntax. And this new syntax can break things in existing code bases.

An example of this is the async/await feature. Rust initially didn’t have the concepts of async and await. But it turns out that these primitives are really helpful. They make it easier to write code that is asynchronous without the code getting unwieldy.

To make it possible to add this feature, we need to add both async and await as keywords. But we also have to be careful that we’re not making old code invalid… code that might’ve used the words async or await as variable names.

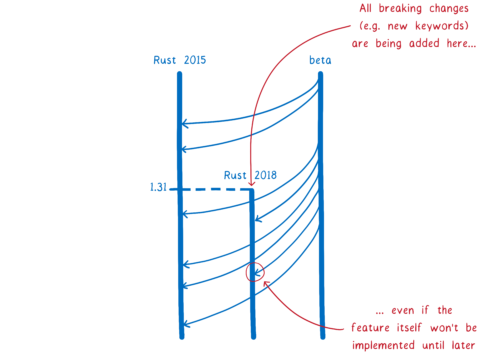

So we’re adding the keywords as part of Rust 2018. Even though the feature hasn’t landed yet, the keywords are now reserved. All of the breaking changes needed for the next three years of development (like adding new keywords) are being made in one go, in Rust 1.31.

Even though there are breaking changes in Rust 2018, that doesn’t mean your code will break. Your code will continue compiling even if it has async or await as a variable name. Unless you tell it otherwise, the compiler assumes you want it to compile your code the same way that it has been up to this point.

But as soon as you want to use one of these new, breaking features, you can opt in to Rust 2018 mode. You just run cargo fix, which will tell you if you need to update your code to use the new features. It will also mostly automate the process of making the changes. Then you can add edition=2018 to your Cargo.toml to opt in and use the new features.

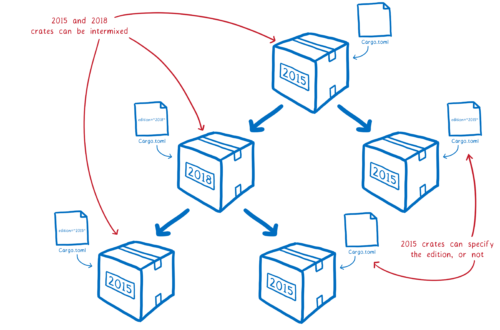

This edition specifier in Cargo.toml doesn’t apply to your whole project… it doesn’t apply to your dependencies. It’s scoped to just the one crate. This means you’ll be able to have crate graphs that have Rust 2015 and Rust 2018 interspersed.

Because of this, even once Rust 2018 is out there, it’s mostly going to look the same as Rust 2015. Most changes will land in both Rust 2018 and Rust 2015. Only the handful of features that require breaking changes won’t pass through.

Rust 2018 isn’t just about changes to the core language, though. In fact, far from it.

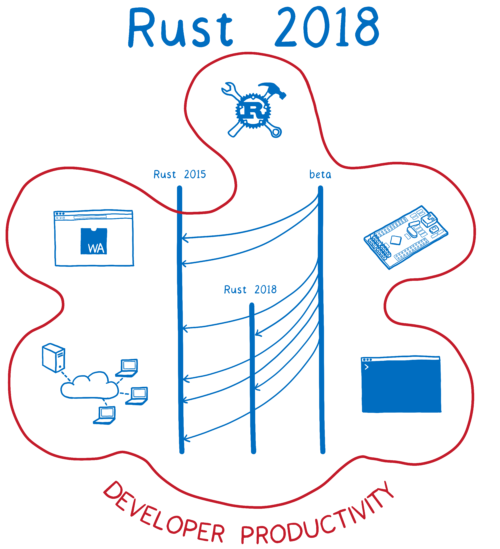

Rust 2018 is a push to make Rust developers more productive. Many productivity wins come from things outside of the core language… things like tooling. They also come from focusing on specific use cases and figuring out how Rust can be the most productive language for those use cases.

So you could think of Rust 2018 as the specifier in Cargo.toml that you use to enable the handful of features that require breaking changes…

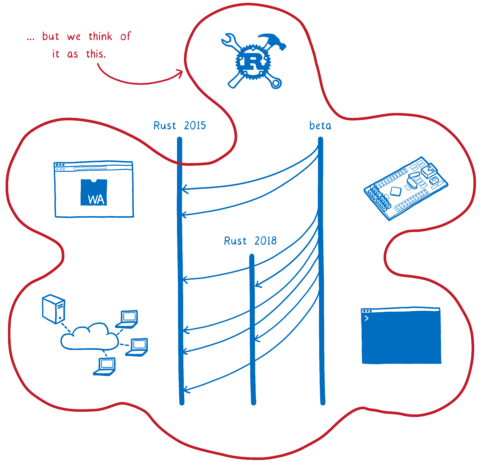

Or you can think about it as a moment in time, where Rust becomes one of the most productive languages you can use in many cases — whenever you need performance, light footprint, or high reliability.

In our minds, it’s the second. So let’s look at all that happened outside of the core language. Then we can dive into the core language itself.

Rust for specific use cases

A programming language can’t be productive by itself, in the abstract. It’s productive when put to some use. Because of this, the team knew we didn’t just need to make Rust as a language or Rust tooling better. We also needed to make it easier to use Rust in particular domains.

In some cases, this meant creating a whole new set of tools for a whole new ecosystem.

In other cases, it meant polishing what was already in the ecosystem and documenting it well so that it’s easy to get up and running.

The Rust team formed working groups focused on four domains:

- WebAssembly

- Embedded applications

- Networking

- Command line tools

WebAssembly

For WebAssembly, the working group needed to create a whole new suite of tools.

Just last year, WebAssembly made it possible to compile languages like Rust to run on the web. Since then, Rust has quickly become the best language for integrating with existing web applications.

Rust is a good fit for web development for two reasons:

- Cargo’s crates ecosystem works in the same way that most web app developers are used to. You pull together a bunch of small modules to form a larger application. This means that it’s easy to use Rust just where you need it.

- Rust has a light footprint and doesn’t require a runtime. This means that you don’t need to ship down a bunch of code. If you have a tiny module doing lots of heavy computational work, you can introduce a few lines of Rust just to make that run faster.

With the web-sys and js-sys crates, it’s easy to call web APIs like fetch or appendChild from Rust code. And wasm-bindgen makes it easy support high-level data types that WebAssembly doesn’t natively support.

Once you’ve coded up your Rust WebAssembly module, there are tools to make it easy to plug it into the rest of your web application. You can use wasm-pack to run these tools automatically, and push your new module up to npm if you want.

Check out the Rust and WebAssembly book to try it yourself.

What’s next?

Now that Rust 2018 has shipped, the working group is figuring out where to take things next. They’ll be working with the community to determine the next areas of focus.

Embedded

For embedded development, the working group needed to make existing functionality stable.

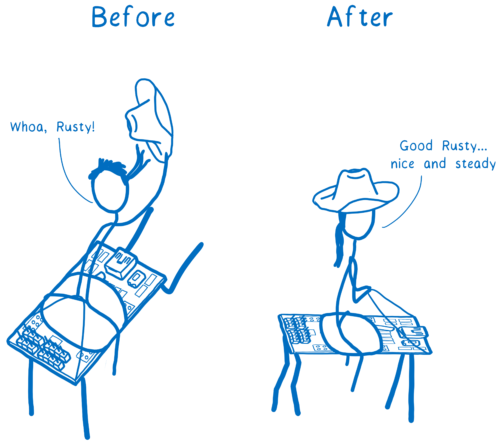

In theory, Rust has always been a good language for embedded development. It gives embedded developers the modern day tooling that they are sorely lacking, and very convenient high-level language features. All this without sacrificing on resource usage. So Rust seemed like a great fit for embedded development.

However, in practice it was a bit of a wild ride. Necessary features weren’t in the stable channel. Plus, the standard library needed to be tweaked for use on embedded devices. That meant that people had to compile their own version of the Rust core crate (the crate which is used in every Rust app to provide Rust’s basic building blocks — intrinsics and primitives).

Together, these two things meant developers had to depend on the nightly version of Rust. And since there were no automated tests for micro-controller targets, nightly would often break for these targets.

To fix this, the working group needed to make sure that necessary features were in the stable channel. We also had to add tests to the CI system for micro-controller targets. This means a person adding something for a desktop component won’t break something for an embedded component.

With these changes, embedded development with Rust moves away from the bleeding edge and towards the plateau of productivity.

Check out the Embedded Rust book to try it yourself.

What’s next?

With this year’s push, Rust has really good support for ARM Cortex-M family of microprocessor cores, which are used in a lot of devices. However, there are lots of architectures used on embedded devices, and those aren’t as well supported. Rust needs to expand to have the same level of support for these other architectures.

Networking

For networking, the working group needed to build a core abstraction into the language—async/await. This way, developers can use idiomatic Rust even when the code is asynchronous.

For networking tasks, you often have to wait. For example, you may be waiting for a response to a request. If your code is synchronous, that means the work will stop—the CPU core that is running the code can’t do anything else until the request comes in. But if you code asynchronously, then the function that’s waiting for the response can go on hold while the CPU core takes care of running other functions.

Coding asynchronous Rust is possible even with Rust 2015. And there are lots of upsides to this. On the large scale, for things like server applications, it means that your code can handle many more connections per server. On the small scale, for things like embedded applications that are running on tiny, single threaded CPUs, it means you can make better use of your single thread.

But these upsides came with a major downside—you couldn’t use the borrow checker for that code, and you would have to write unidiomatic (and somewhat confusing) Rust. This is where async/await comes in. It gives the compiler the information it needs to borrow check across asynchronous function calls.

The keywords for async/await were introduced in 1.31, although they aren’t currently backed by an implementation. Much of that work is done, and you can expect the feature to be available in an upcoming release.

What’s next?

Beyond just enabling productive low-level development for networking applications, Rust could enable more productive development at a higher level.

Many servers need to do the same kinds of tasks. They need to parse URLs or work with HTTP. If these were turned into components—common abstractions that could be shared as crates—then it would be easy to plug them together to form all sorts of different servers and frameworks.

To drive the component development process, the Tide framework is providing a test bed for, and eventually example usage of, these components.

Command line tools

For command line tools, the working group needed to bring together smaller, low-level libraries into higher level abstractions, and polish some existing tools.

For some CLI scripts, you really want to use bash. For example, if you just need to call out to other shell tools and pipe data between them, then bash is best.

But Rust is a great fit for a lot of other kinds of CLI tools. For example, it’s great if you are building a complex tool like ripgrep or building a CLI tool on top of an existing library’s functionality.

Rust doesn’t require a runtime and allows you to compile to a single static binary, which makes it easy to distribute. And you get high-level abstractions that you don’t get with other languages like C and C++, so that already makes Rust CLI developers productive.

What did the working group need to make this better still? Even higher-level abstractions.

With these higher-level abstractions, it’s quick and easy to assemble a production ready CLI.

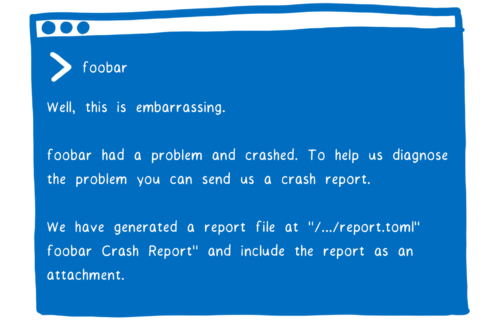

An example of one of these abstractions is the human panic library. Without this library, if your CLI code panics, it probably outputs the entire back trace. But that’s not very helpful for your end users. You could add custom error handling, but that requires effort.

If you use human panic, then the output will be automatically routed to an error dump file. What the user will see is a helpful message suggesting that they report the issue and upload the error dump file.

The working group also made it easier to get started with CLI development. For example, the confy library will automate a lot of setup for a new CLI tool. It only asks you two things:

- What’s the name of your application?

- What are configuration options you want to expose (which you define as a struct that can be serialized and deserialized)?

From that, confy will figure out the rest for you.

What’s next?

The working group abstracted away a lot of different tasks that are common between CLIs. But there’s still more that could be abstracted away. The working group will be making more of these high level libraries, and fixing more paper cuts as they go.

Rust tooling

When you experience a language, you experience it through tools. This starts with the editor that you use. It continues through every stage of the development process, and through maintenance.

This means that a productive language depends on productive tooling.

Here are some tools (and improvements to Rust’s existing tooling) that were introduced as part of Rust 2018.

IDE support

Of course, productivity hinges on fluidly getting code from your mind to the screen quickly. IDE support is critical to this. To support IDEs, we need tools that can tell the IDE what Rust code actually means — for example, to tell the IDE what strings make sense for code completion.

In the Rust 2018 push, the community focused on the features that IDEs needed. With Rust Language Server and IntelliJ Rust, many IDEs now have fluid Rust support.

Faster compilation

With compilation, faster means more productive. So we’ve made the compiler faster.

Before, when you would compile a Rust crate, the compiler would recompile every single file in the crate. But now, with incremental compilation, the compiler is smart and only recompiles the parts that have changed. This, along with other optimizations, has made the Rust compiler much faster.

rustfmt

Productivity also means not having to fix style nits (and never having to argue over formatting rules).

The rustfmt tool helps with this by automatically reformatting your code using a default code style (which the community reached consensus on). Using rustfmt ensures that all of your Rust code conforms to the same style, like clang format does for C++ and Prettier does for JavaScript.

Clippy

Sometimes it’s nice to have an experienced advisor by your side… giving you tips on best practices as you code. That’s what Clippy does —it reviews your code as you go and tells you how to make that code more idiomatic.

rustfix

But if you have an older code base that uses outmoded idioms, then just getting tips and correcting the code yourself can be tedious. You just want someone to go into your code base and make the corrections.

For these cases, rustfix will automate the process. It will both apply lints from tools like Clippy and update older code to match Rust 2018 idioms.

Changes to Rust itself

These changes in the ecosystem have brought lots of productivity wins. But some productivity issues could only be fixed with changes to the language itself.

As I talked about in the intro, most of the language changes are completely compatible with existing Rust code. These changes are all part of Rust 2018. But because they don’t break any code, they also work in any Rust code… even if that code doesn’t use Rust 2018.

Let’s look at a few of the big language features that were added to all editions. Then we can look at the small list of Rust 2018-specific features.

New language features for all editions

Here’s a small sample of the big new language features that are (or will be) in all language editions.

More precise borrow checking (e.g. Non-Lexical Lifetimes)

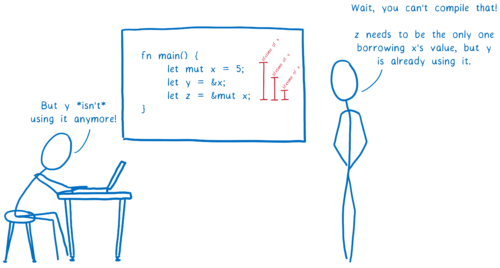

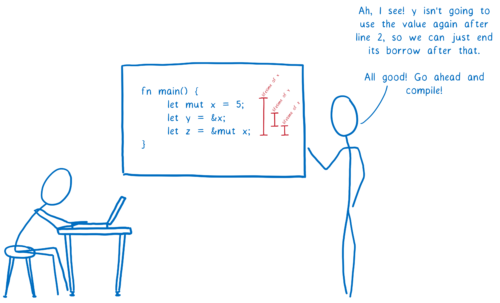

One big selling point for Rust is the borrow checker. The borrow checker helps ensure that your code is memory safe. But it has also been a pain point for new Rust developers.

Part of that is learning new concepts. But there was another big part… the borrow checker would sometimes reject code that seemed like it should work, even to those who understood the concepts.

This is because the lifetime of a borrow was assumed to go all the way to the end of its scope — for example, to the end of the function that the variable is in.

This meant that even though the variable was done with the value and wouldn’t try to access it anymore, other variables were still denied access to it until the end of the function.

To fix this, we’ve made the borrow checker smarter. Now it can see when a variable is actually done using a value. If it is done, then it doesn’t block other borrowers from using the data.

While this is only available in Rust 2018 as of today, it will be available in all editions in the near future. I’ll be writing more about all of this soon.

Procedural macros on stable Rust

Macros in Rust have been around since before Rust 1.0. But with Rust 2018, we’ve made some big improvements, like introducing procedural macros.

With procedural macros, it’s kind of like you can add your own syntax to Rust.

Rust 2018 brings two kinds of procedural macros:

Function-like macros

Function-like macros allow you to have things that look like regular function calls, but that are actually run during compilation. They take in some code and spit out different code, which the compiler then inserts into the binary.

They’ve been around for a while, but what you could do with them was limited. Your macro could only take the input code and run a match statement on it. It didn’t have access to look at all of the tokens in that input code.

But with procedural macros, you get the same input that a parser gets — a token stream. This means can create much more powerful function-like macros.

Attribute-like macros

If you’re familiar with decorators in languages like JavaScript, attribute macros are pretty similar. They allow you to annotate bits of code in Rust that should be preprocessed and turned into something else.

The derive macro does exactly this kind of thing. When you put derive above a struct, the compiler will take that struct in (after it has been parsed as a list of tokens) and fiddle with it. Specifically, it will add a basic implementation of functions from a trait.

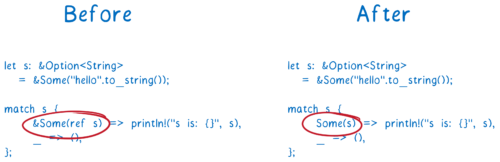

More ergonomic borrowing in matching

This change is pretty straight-forward.

Before, if you wanted to borrow something and tried to match on it, you had to add some weird looking syntax:

But now, you don’t need the &Some(ref s) anymore. You can just write Some(s), and Rust will figure it out from there.

New features specific to Rust 2018

The smallest part of Rust 2018 are the features specific to it. Here are the small handful of changes that using the Rust 2018 edition unlocks.

Keywords

There are a few keywords that have been added to Rust 2018.

trykeywordasync/awaitkeyword

These features haven’t been fully implemented yet, but the keywords are being added in Rust 1.31. This means we don’t have to introduce new keywords (which would be a breaking change) in the future, once the features behind these keywords are implemented.

The module system

One big pain point for developers learning Rust is the module system. And we could see why. It was hard to reason about how Rust would choose which module to use.

To fix this, we made a few changes to the way paths work in Rust.

For example, if you imported a crate, you could use it in a path at the top level. But if you moved any of the code to a submodule, then it wouldn’t work anymore.

// top level module

extern crate serde;

// this works fine at the top level

impl serde::Serialize for MyType { ... }

mod foo {

// but it does *not* work in a sub-module

impl serde::Serialize for OtherType { ... }

}

Another example is the prefix ::, which used to refer to either the crate root or an external crate. It could be hard to tell which.

We’ve made this more explicit. Now, if you want to refer to the crate root, you use the prefix crate:: instead. And this is just one of the path clarity improvements we’ve made.

If you have existing Rust code and you want it to use Rust 2018, you’ll very likely need to update it for these new module paths. But that doesn’t mean that you’ll need to manually update your code. Run cargo fix before you add the edition specifier to Cargo.toml and rustfix will make all the changes for you.

Learn More

Learn all about this edition in the Rust 2018 edition guide.

About Lin Clark

Lin works in Advanced Development at Mozilla, with a focus on Rust and WebAssembly.

12 comments