Roughly a year ago at Mozilla we started an effort to improve Firefox stability on Linux. This effort quickly became an example of good synergies between FOSS projects.

Every time Firefox crashes, the user can send us a crash report which we use to analyze the problem and hopefully fix it:

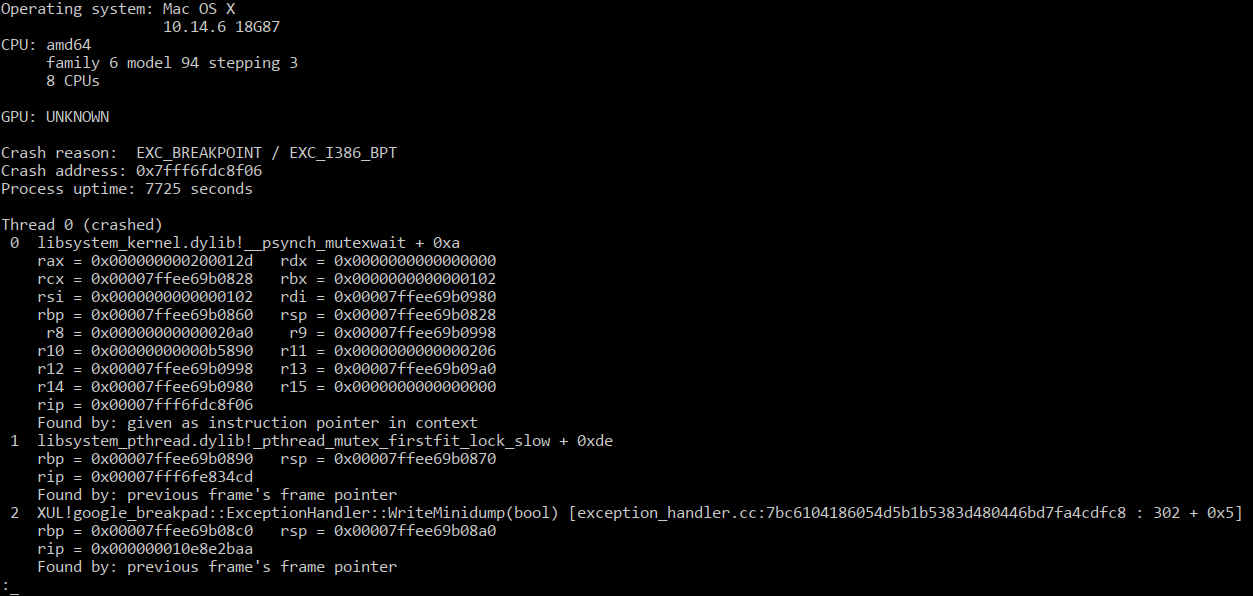

This report contains, among other things, a minidump: a small snapshot of the process memory at the time it crashed. This includes the contents of the processor’s registers as well as data from the stacks of every thread.

Here’s what this usually looks like:

If you’re familiar with core dumps, then minidumps are essentially a smaller version of them. The minidump format was originally designed at Microsoft and Windows has a native way of writing out minidumps. On Linux, we use Breakpad for this task. Breakpad originated at Google for their software (Picasa, Google Earth, etc…) but we have forked, heavily modified for our purposes and recently partly rewrote it in Rust.

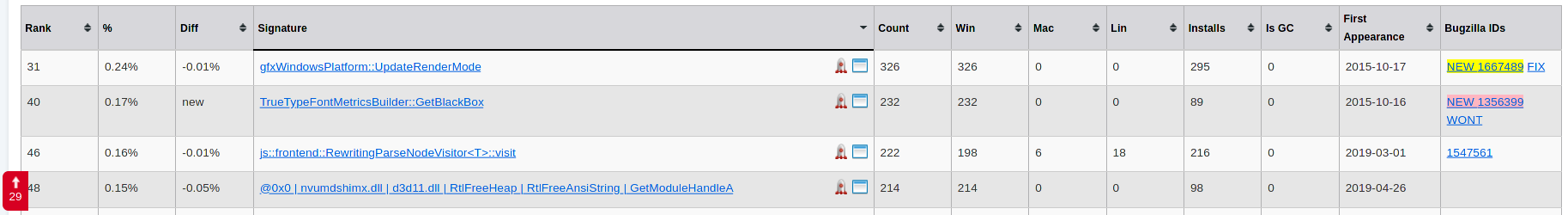

Once the user submits a crash report, we have a server-side component – called Socorro – that processes it and extracts a stack trace from the minidump. The reports are then clustered based on the top method name of the stack trace of the crashing thread. When a new crash is spotted we assign it a bug and start working on it. See the picture below for an example of how crashes are grouped:

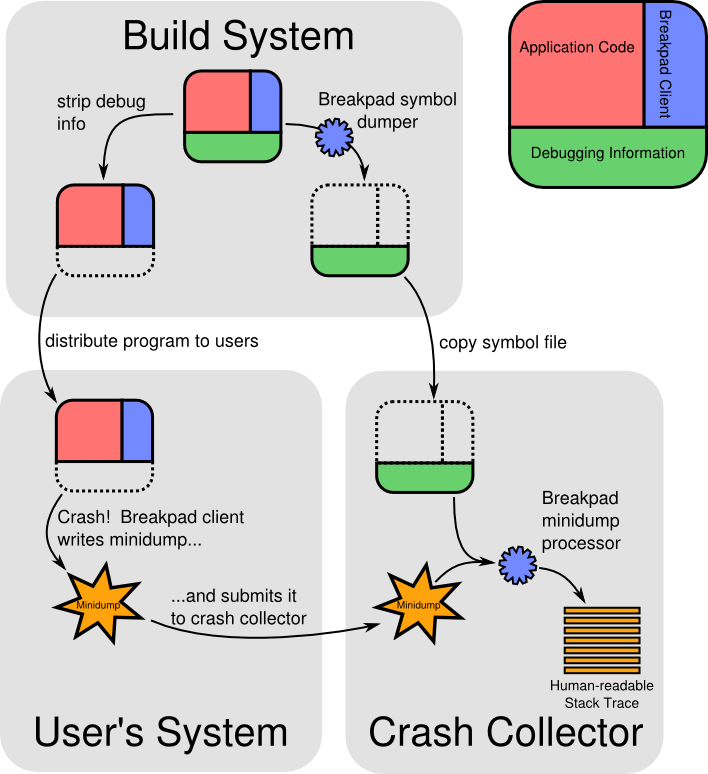

To extract a meaningful stack trace from a minidump two more things are needed: unwinding information and symbols. The unwinding information is a set of instructions that describe how to find the various frames in the stack given an instruction pointer. Symbol information contains the names of the functions corresponding to a given range of addresses as well as the source files they come from and the line numbers a given instruction corresponds to.

In regular Firefox releases, we extract this information from the build files and store it into symbol files in Breakpad standard format. Equipped with this information Socorro can produce a human-readable stack trace. The whole flow can be seen below:

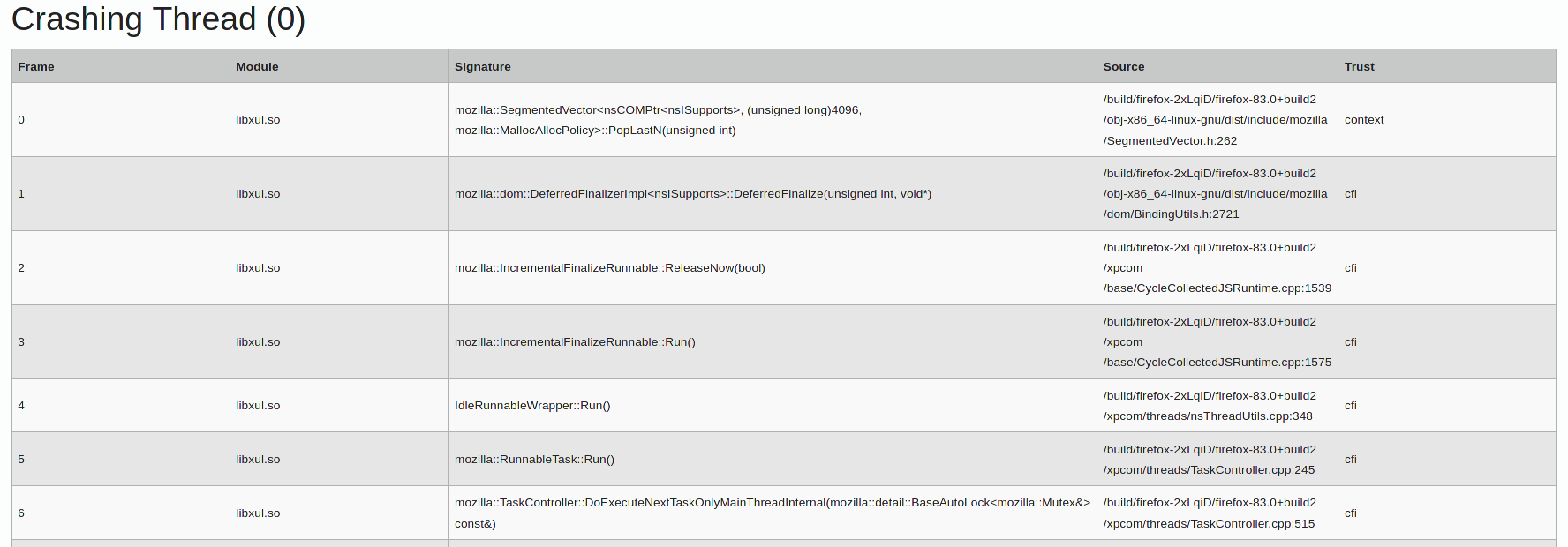

Here’s an example of a proper stack trace:

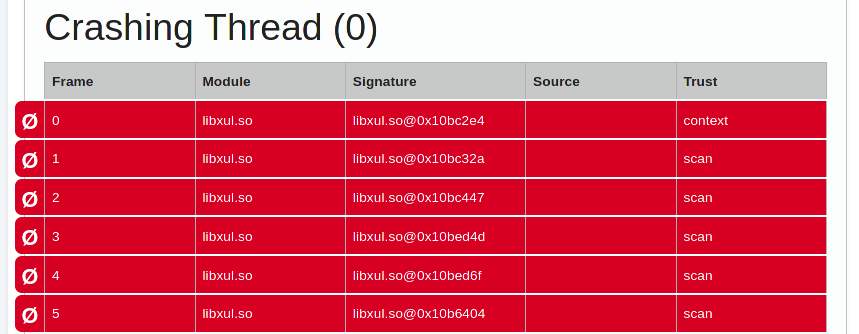

If Socorro doesn’t have access to the appropriate symbol files for a crash the resulting trace contains only addresses and isn’t very helpful:

When it comes to Linux things work differently than on other platforms: most of our users do not install our builds, they install the Firefox version that comes packaged for their favourite distribution.

This posed a significant problem when dealing with stability issues on Linux: for the majority of our crash reports, we couldn’t produce high-quality stack traces because we didn’t have the required symbol information. The Firefox builds that submitted the reports weren’t done by us. To make matters worse, Firefox depends on a number of third-party packages (such as GTK, Mesa, FFmpeg, SQLite, etc.). We wouldn’t get good stack traces if a crash occurred in one of these packages instead of Firefox itself because we didn’t have symbols for them either.

To address this issue, we started scraping debug information for Firefox builds and their dependencies from the package repositories of multiple distributions: Arch, Debian, Fedora, OpenSUSE and Ubuntu. Since every distribution does things a little bit differently, we had to write distro-specific scripts that would go through the list of packages in their repositories and find the associated debug information (the scripts are available here). This data is then fed into a tool that extracts symbol files from the debug information and uploads it to our symbol server.

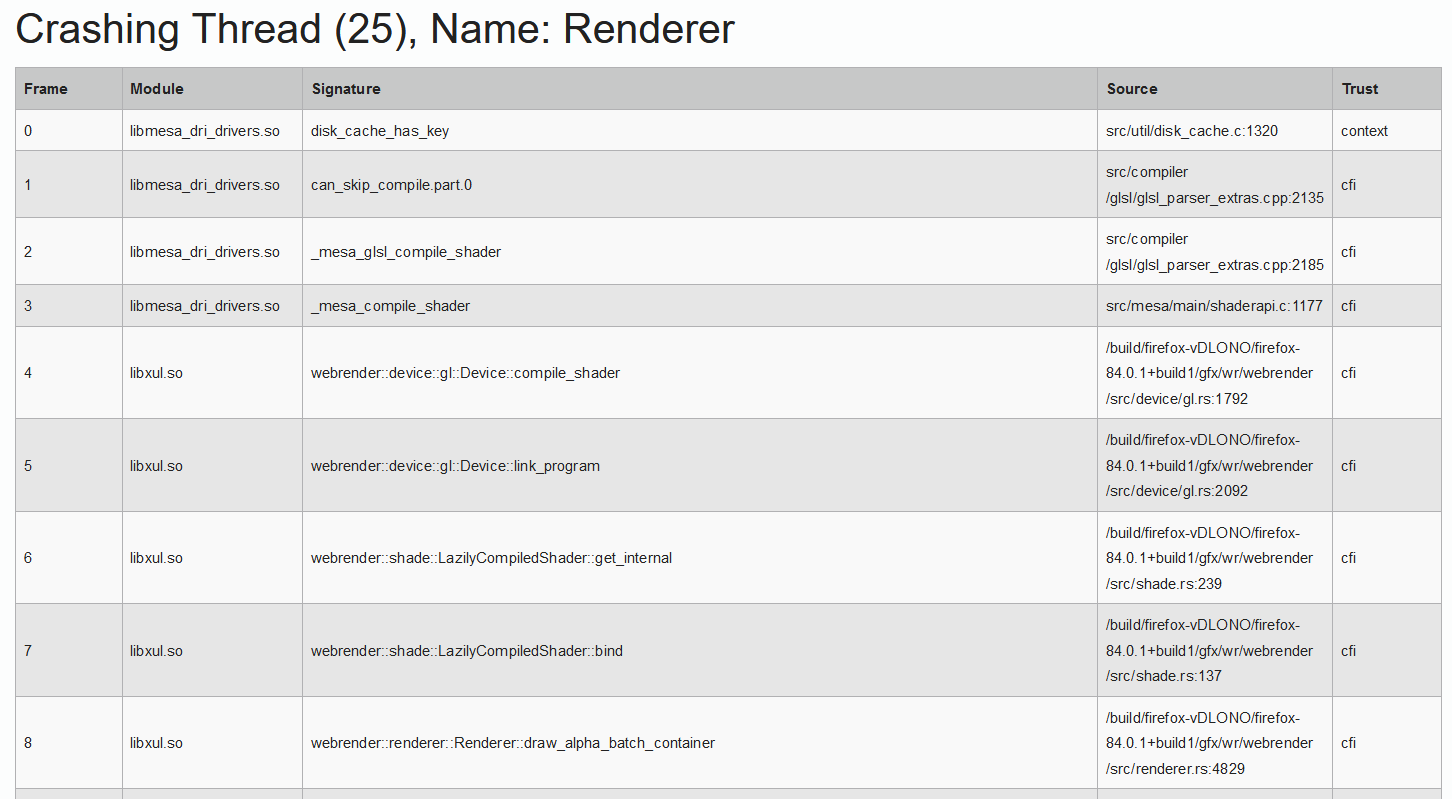

With that information now available, we were able to analyze >99% of the crash reports we received from Linux users, up from less than 20%. Here’s an example of a high-quality trace extracted from a distro-packaged version of Firefox. We haven’t built any of the libraries involved yet the function names are present and so are the file and line numbers of the affected code:

The importance of this cannot be overestimated: Linux users tend to be more tech-savvy and are more likely to help us solve issues, so all those reports were a treasure trove for improving stability even for other operating systems (Windows, Mac, Android, etc). In particular, we often identified Fission bugs on Linux first.

The first effect of this newfound ability to inspect Linux crashes is that it greatly sped up our response time to Linux-specific issues, and often allowed us to identify problems in the Nightly and Beta versions of Firefox before they reached users on the release channel.

We could also quickly identify issues in bleeding-edge components such as WebRender, WebGPU, Wayland and VA-API video acceleration; oftentimes providing a fix within days of the change that triggered the issue.

We didn’t stop there: we could now identify distro-specific issues and regressions. This allowed us to inform package maintainers of the problems and have them resolved quickly. For example, we were able to identify a Debian-specific issue only two weeks after it was introduced and fixed it right away. The crash was caused by a modification made by Debian to one of Firefox dependencies that could cause a crash on startup, it’s filed under bug 1679430 if you’re curious about the details.

Another good example comes from Fedora: they had been using their own crash reporting system (ABRT) to catch Firefox crashes in their Firefox builds, but given the improvements on our side they started sending Firefox crashes our way instead.

We could also finally identify regressions and issues in our dependencies. This allowed us to communicate the issues upstream and sometimes even contributed fixes, benefiting both our users and theirs.

For example, at some point, Debian updated the fontconfig package by backporting an upstream fix for a memory leak. Unfortunately, the fix contained a bug that would crash Firefox and possibly other software too. We spotted the new crash only six days after the change landed in Debian sources and only a couple of weeks afterwards the issue had been fixed both upstream and in Debian. We sent reports and fixes to other projects too including Mesa, GTK, glib, PCSC, SQLite and more.

Nightly versions of Firefox also include a tool to spot security-sensitive issues: the probabilistic heap checker. This tool randomly pads a handful of memory allocations in order to detect buffer overflows and use-after-free accesses. When it detects one of these, it sends us a very detailed crash report. Given Firefox’s large user-base on Linux, this allowed us to spot some elusive issues in upstream projects and report them.

This also exposed some limitations in the tools we use for crash analysis, so we decided to rewrite them in Rust largely relying on the excellent crates developed by Sentry. The resulting tools were dramatically faster than our old ones, used a fraction of the memory and produced more accurate results. Code flowed both ways: we contributed improvements to their crates (and their dependencies) while they expanded their APIs to address our new use-cases and fixed the issues we discovered.

Another pleasant side-effect of this work is that Thunderbird now also benefits from the improvement we made for Firefox.

This goes on to show how collaboration between FOSS projects not only benefits their users but ultimately improves the whole ecosystem and the broader community that relies on it.

Special thanks to Calixte Denizet, Nicholas Nethercote, Jan Auer and all the others that contributed to this effort!