Smart home devices can make busy lives a little easier, but they also require you to give up control of your usage data to companies for the devices to function. In a recent article from the New York Times’ Privacy Project about protecting privacy online, the author recommended people to not buy Internet of Things (IoT) devices unless they’re “willing to give up a little privacy for whatever convenience they provide.”

This is sound advice since smart home companies can not only know if you’re at home when you say you are, they’ll soon be able to listen for your sniffles through their always-listening microphones and recommend sponsored cold medicine from affiliated vendors. Moreover, by both requiring that users’ data go through their servers and by limiting interoperability between platforms, leading smart home companies are chipping away at people’s ability to make real, nuanced technology choices as consumers.

At Mozilla, we believe that you should have control over your devices and the data that smart home devices create about you. You should own your data, you should have control over how it’s shared with others, and you should be able to contest when a data profile about you is inaccurate.

Mozilla WebThings follows the privacy by design framework, a set of principles developed by Dr. Ann Cavoukian, that takes users’ data privacy into account throughout the whole design and engineering lifecycle of a product’s data process. Prioritizing people over profits, we offer an alternative approach to the Internet of Things, one that’s private by design and gives control back to you, the user.

User Research Findings on Privacy and IoT Devices

Before we look at the design of Mozilla WebThings, let’s talk briefly about how people think about their privacy when they use smart home devices and why we think it’s essential that we empower people to take charge.

Today, when you buy a smart home device, you are buying the convenience of being able to control and monitor your home via the Internet. You can turn a light off from the office. You can see if you’ve left your garage door open. Prior research has shown that users are passively, and sometimes actively, willing to trade their privacy for the convenience of a smart home device. When it seems like there’s no alternative between having a potentially useful device or losing their privacy, people often uncomfortably choose the former.

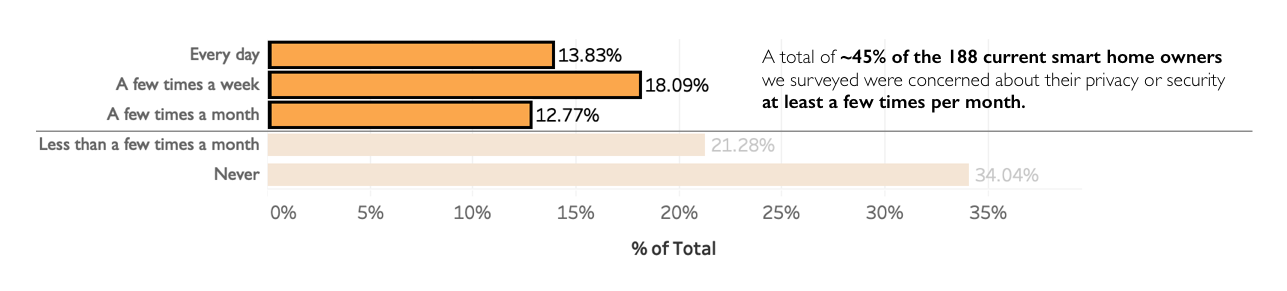

Still, although people are buying and using smart home devices, it does not mean they’re comfortable with this status quo. In one of our recent user research surveys, we found that almost half (45%) of the 188 smart home owners we surveyed were concerned about the privacy or security of their smart home devices.

Last Fall 2018, our user research team conducted a diary study with eleven participants across the United States and the United Kingdom. We wanted to know how usable and useful people found our WebThings software. So we gave each of our research participants some Raspberry Pis (loaded with the Things 0.5 image) and a few smart home devices.

We watched, either in-person or through video chat, as each individual walked through the set up of their new smart home system. We then asked participants to write a ‘diary entry’ every day to document how they were using the devices and what issues they came across. After two weeks, we sat down with them to ask about their experience. While a couple of participants who were new to smart home technology were ecstatic about how IoT could help them in their lives, a few others were disappointed with the lack of reliability of some of the devices. The rest fell somewhere in between, wanting improvements such as more sophisticated rules functionality or a phone app to receive notifications on their iPhones.

We also learned more about people’s attitudes and perceptions around the data they thought we were collecting about them. Surprisingly, all eleven of our participants expected data to be collected about them. They had learned to expect data collection, as this has become the prevailing model for other platforms and online products. A few thought we would be collecting data to help improve the product or for research purposes. However, upon learning that no data had been collected about their use, a couple of participants were relieved that they would have one less thing, data, to worry about being misused or abused in the future.

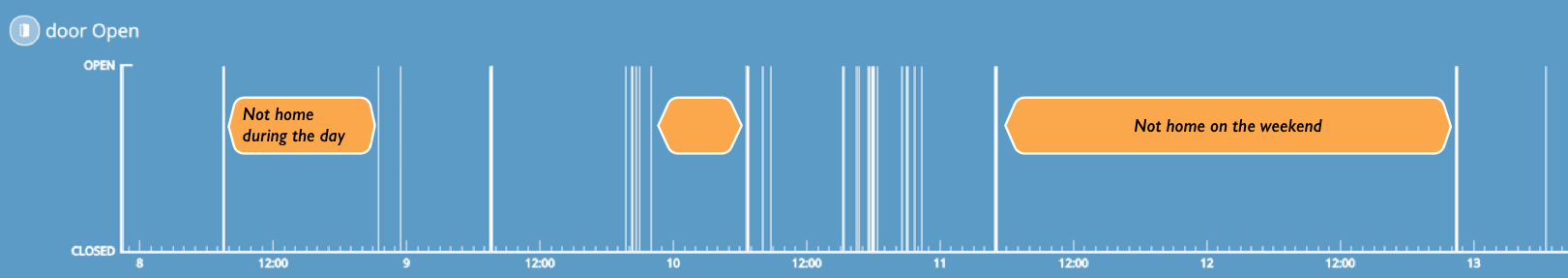

By contrast, others said they weren’t concerned about data collection; they did not think companies could make use of what they believed was menial data, such as when they were turning a light on or off. They did not see the implications of how collected data could be used against them. This showed us that we can improve on how we demonstrate to users what others can learn from your smart home data. For example, one can find out when you’re not home based on when your door has opened and closed.

From our user research, we’ve learned that people are concerned about the privacy of their smart home data. And yet, when there’s no alternative, they feel the need to trade away their privacy for convenience. Others aren’t as concerned because they don’t see the long-term implications of collected smart home data. We believe privacy should be a right for everyone regardless of their socioeconomic or technical background. Let’s talk about how we’re doing that.

Decentralizing Data Management Gives Users Privacy

Vendors of smart home devices have architected their products to be more of service to them than to their customers. Using the typical IoT stack, in which devices don’t easily interoperate, they can build a robust picture of user behavior, preferences, and activities from data they have collected on their servers.

Take the simple example of a smart light bulb. You buy the bulb, and you download a smartphone app. You might have to set up a second box to bridge data from the bulb to the Internet and perhaps a “user cloud subscription account” with the vendor so that you can control the bulb whether you’re home or away. Now imagine five years into the future when you have installed tens to hundreds of smart devices including appliances, energy/resource management devices, and security monitoring devices. How many apps and how many user accounts will you have by then?

The current operating model requires you to give your data to vendor companies for your devices to work properly. This, in turn, requires you to work with or around companies and their walled gardens.

Mozilla’s solution puts the data back in the hands of users. In Mozilla WebThings, there are no company cloud servers storing data from millions of users. User data is stored in the user’s home. Backups can be stored anywhere. Remote access to devices occurs from within one user interface. Users don’t need to download and manage multiple apps on their phones, and data is tunneled through a private, HTTPS-encrypted subdomain that the user creates.

The only data Mozilla receives are the instances when a subdomain pings our server for updates to the WebThings software. And if a user only wants to control their devices locally and not have anything go through the Internet, they can choose that option too.

Decentralized distribution of WebThings Gateways in each home means that each user has their own private “data center”. The gateway acts as the central nervous system of their smart home. By having smart home data distributed in individual homes, it becomes more of a challenge for unauthorized hackers to attack millions of users. This decentralized data storage and management approach offers a double advantage: it provides complete privacy for user data, and it securely stores that data behind a firewall that uses best-of-breed https encryption.

The figure below compares Mozilla’s approach to that of today’s typical smart home vendor.

Mozilla’s approach gives users an alternative to current offerings, providing them with data privacy and the convenience that IoT devices can provide.

Ongoing Efforts to Decentralize

In designing Mozilla WebThings, we have consciously insulated users from servers that could harvest their data, including our own Mozilla servers, by offering an interoperable, decentralized IoT solution. Our decision to not collect data is integral to our mission and additionally feeds into our Emerging Technology organization’s long-term interest in decentralization as a means of increasing user agency.

WebThings embodies our mission to treat personal security and privacy on the Internet as a fundamental right, giving power back to users. From Mozilla’s perspective, decentralized technology has the ability to disrupt centralized authorities and provide more user agency at the edges, to the people.

Decentralization can be an outcome of social, political, and technological efforts to redistribute the power of the few and hand it back to the many. We can achieve this by rethinking and redesigning network architecture. By enabling IoT devices to work on a local network without the need to hand data to connecting servers, we decentralize the current IoT power structure.

With Mozilla WebThings, we offer one example of how a decentralized, distributed system over web protocols can impact the IoT ecosystem. Concurrently, our team has an unofficial draft Web Thing API specification to support standardized use of the web for other IoT device and gateway creators.

While this is one way we are making strides to decentralize, there are complementary projects, ranging from conceptual to developmental stages, with similar aims to put power back into the hands of users. Signals from other players, such as FreedomBox Foundation, Daplie, and Douglass, indicate that individuals, households, and communities are seeking the means to govern their own data.

By focusing on people first, Mozilla WebThings gives people back their choice: whether it’s about how private they want their data to be or which devices they want to use with their system.

This project is an ongoing effort. If you want to learn more or get involved, check out the Mozilla WebThings Documentation, you can contribute to our documentation or get started on your own web things or Gateway.

If you live in the Bay Area, you can find us this weekend at Maker Faire Bay Area (May 17-19). Stop by our table. Or follow @mozillaiot to learn about upcoming workshops and demos.

About Josephine Lau

UX Researcher at Strategic Foresight, Emerging Technologies.

More articles by Josephine Lau…

About Ryan Hogan

Business Analyst - Strategic Foresight