Threats to users’ privacy and security are growing. At Mozilla, we closely track these threats. We believe we have a duty to do everything we can to protect Firefox users and their data.

We’re taking on the companies and organizations that want to secretly collect and sell user data. This is why we added tracking protection and created the Facebook container extension. And you’ll be seeing us do more things to protect our users over the coming months.

Two more protections we’re adding to that list are:

- DNS over HTTPS, a new IETF standards effort that we’ve championed

- Trusted Recursive Resolver, a new secure way to resolve DNS that we’ve partnered with Cloudflare to provide

With these two initiatives, we’re closing data leaks that have been part of the domain name system since it was created 35 years ago. And we’d like your help in testing them. So let’s look at how DNS over HTTPS and Trusted Recursive Resolver protect our users.

But first, let’s look at how web pages move around the Internet.

If you already know how DNS and HTTPS work, you can skip to how DNS over HTTPS helps.

A brief HTTP crash course

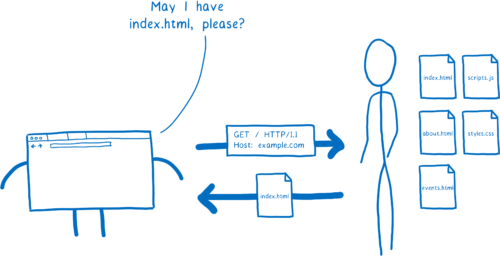

When people explain how a browser downloads a web page, they usually explain it this way:

- Your browser makes a GET request to a server.

- The server sends a response, which is a file containing HTML.

This system is called HTTP.

But this diagram is a little oversimplified. Your browser doesn’t talk directly to the server. That’s because they probably aren’t close to each other.

Instead, the server could be thousands of miles away. And there’s likely no direct link between your computer and the server.

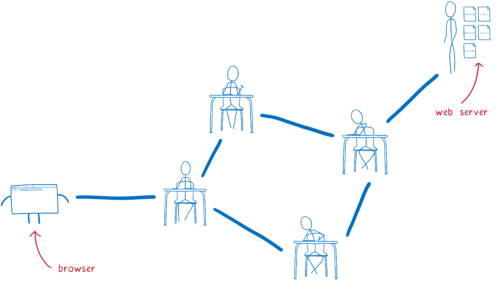

So this request needs to get from the browser to that server, and it will go through multiple hands before it gets there. And the same is true for the response coming back from the server.

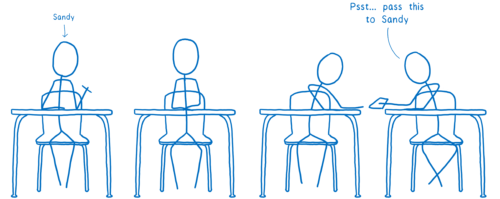

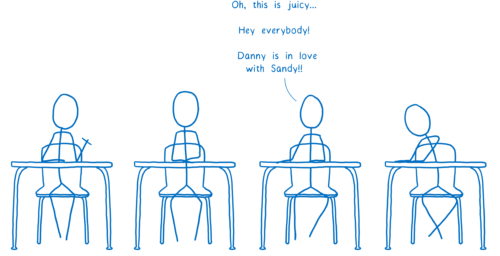

I think of this like kids passing notes to each other in class. On the outside, the note will say who it’s supposed to go to. The kid who wrote the note will pass it to their neighbor. Then that next kid passes it to one of their neighbors — probably not the eventual recipient, but someone who’s in that direction.

The problem with this is that anyone along the path can open up the note and read it. And there’s no way to know in advance which path the note is going to take, so there’s no telling what kind of people will have access to it.

It could end up in the hands of people who do harmful things…

Like sharing the contents of the note with everyone.

Or changing the response.

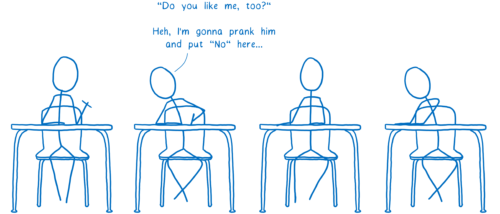

To fix these issues, a new, secure version of HTTP was created. This is called HTTPS. With HTTPS, it’s kind of like each message has a lock on it.

Both the browser and the server know the combination to that lock, but no one in between does.

With this, even if the messages go through multiple routers in between, only you and the web site will actually be able to read the contents.

This solves a lot of the security issues. But there are still some messages going between your browser and the server that aren’t encrypted. This means people along the way can still pry into what you’re doing.

One place where data is still exposed is in setting up the connection to the server. When you send your initial message to the server, you send the server name as well (in a field called “Server Name Indication”). This lets server operators run multiple sites on the same machine while still knowing who you are trying to talk to. This initial request is part of setting up encryption, but the initial request itself isn’t encrypted.

The other place where data is exposed is in DNS. But what is DNS?

DNS: the Domain Name System

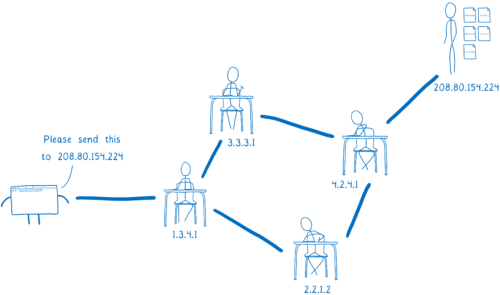

In the passing notes metaphor above, I said that the name of the recipient had to be on the outside of the note. This is true for HTTP requests too… they need to say who they are going to.

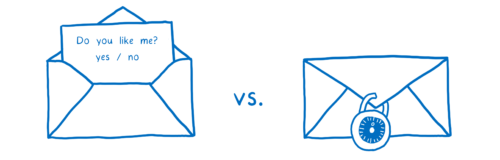

But you can’t use a name for them. None of the routers would know who you were talking about. Instead, you have to use an IP address. That’s how the routers in between know which server you want to send your request to.

This causes a problem. You don’t want users to have to remember your site’s IP address. Instead, you want to be able to give your site a catchy name… something that users can remember.

This is why we have the domain name system (DNS). Your browser uses DNS to convert the site name to an IP address. This process — converting the domain name to an IP address — is called domain name resolution.

How does the browser know how to do this?

One option would be to have a big list, like a phone book in the browser. But as new web sites came online, or as sites moved to new servers, it would be hard to keep that list up-to-date.

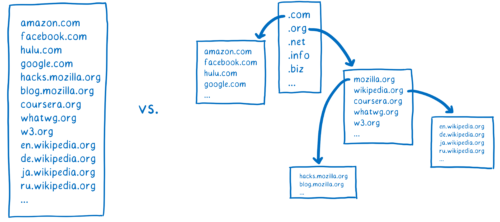

So instead of having one list which keeps track of all of the domain names, there are lots of smaller lists that are linked to each other. This allows them to be managed independently.

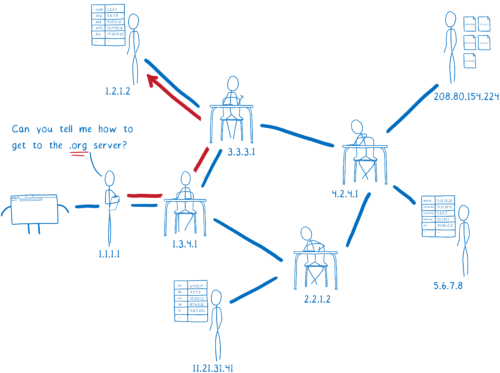

In order to get the IP address that corresponds to a domain name, you have to find the list that contains that domain name. Doing this is kind of like a treasure hunt.

What would this treasure hunt look like for a site like the English version of wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org?

We can split this domain into parts.

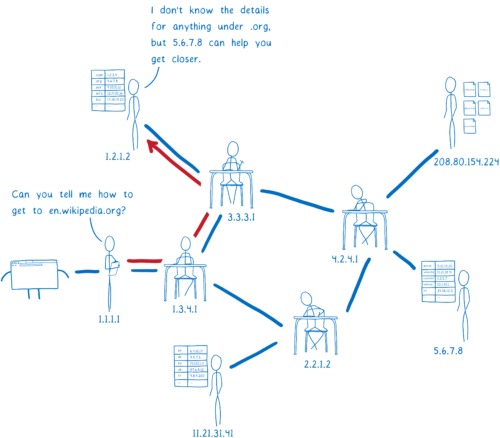

With these parts, we can hunt for the list that contains the IP address for the site. We need some help in our quest, though. The tool that will go on this hunt for us and find the IP address is called a resolver.

First, the resolver talks to a server called the Root DNS. It knows of a few different Root DNS servers, so it sends the request to one of them. The resolver asks the Root DNS where it can find more info about addresses in the .org top-level domain.

The Root DNS will give the resolver an address for a server that knows about .org addresses.

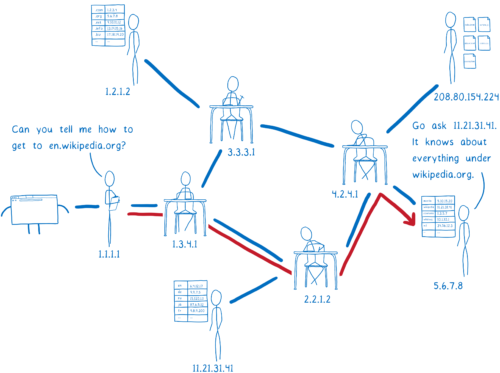

This next server is called a top-level domain (TLD) name server. The TLD server knows about all of the second-level domains that end with .org.

It doesn’t know anything about the subdomains under wikipedia.org, though, so it doesn’t know the IP address for en.wikipedia.org.

The TLD name server will tell the resolver to ask Wikipedia’s name server.

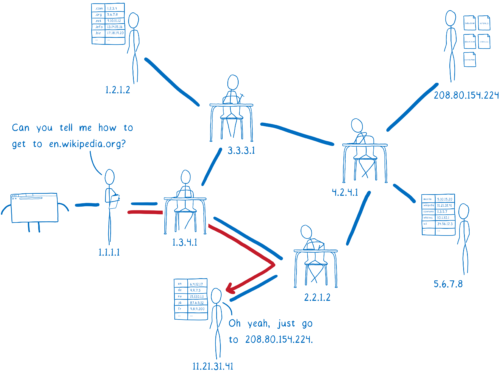

The resolver is almost done now. Wikipedia’s name server is what’s called the authoritative server. It knows about all of the domains under wikipedia.org. So this server knows about en.wikipedia.org, and other subdomains like the German version, de.wikipedia.org. The authoritative server tells the resolver which IP address has the HTML files for the site.

The resolver will return the IP address for en.wikipedia.org to the operating system.

This process is called recursive resolution, because you have to go back and forth asking different servers what’s basically the same question.

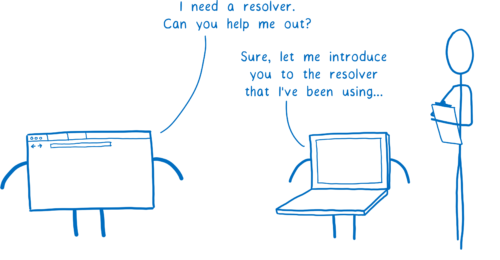

I said we need a resolver to help us in our quest. But how does the browser find this resolver? In general, it asks the computer’s operating system to set it up with a resolver that can help.

How does the operating system know which resolver to use? There are two possible ways.

You can configure your computer to use a resolver you trust. But very few people do this.

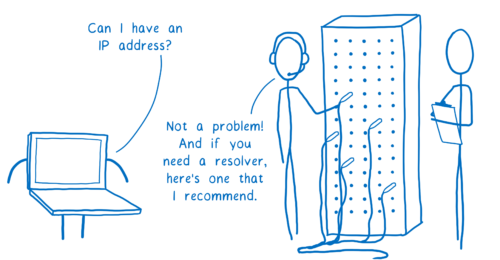

Instead, most people just use the default. And by default, the OS will just use whatever resolver the network told it to. When the computer connects to the network and gets its IP address, the network recommends a resolver to use.

This means that the resolver that you’re using can change multiple times per day. If you head to the coffee shop for an afternoon work session, you’re probably using a different resolver than you were in the morning. And this is true even if you have configured your own resolver, because there’s no security in the DNS protocol.

How can DNS be exploited?

So how can this system make users vulnerable?

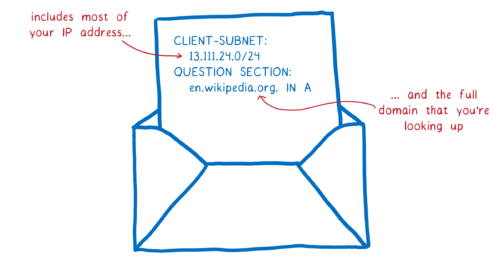

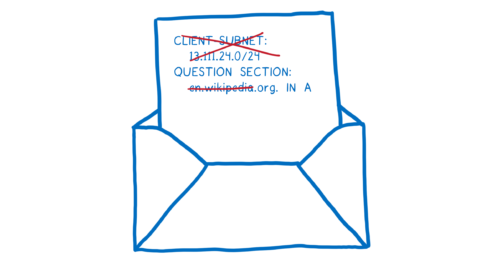

Usually a resolver will tell each DNS server what domain you are looking for. This request sometimes includes your full IP address. Or if not your full IP address, increasingly often the request includes most of your IP address, which can easily be combined with other information to figure out your identity.

This means that every server that you ask to help with domain name resolution sees what site you’re looking for. But more than that, it also means that anyone on the path to those servers sees your requests, too.

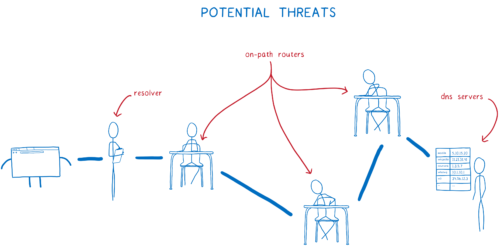

There are a few ways that this system puts users’ data at risk. The two major risks are tracking and spoofing.

Tracking

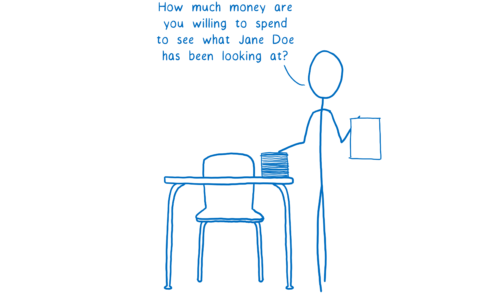

Like I said above, it’s easy to take the full or partial IP address info and figure out who’s asking for that web site. This means that the DNS server and anyone along the path to that DNS server — called on-path routers — can create a profile of you. They can create a record of all of the web sites that they’ve seen you look up.

And that data is valuable. Many people and companies will pay lots of money to see what you are browsing for.

Even if you didn’t have to worry about the possibly nefarious DNS servers or on-path routers, you still risk having your data harvested and sold. That’s because the resolver itself — the one that the network gives to you — could be untrustworthy.

Even if you trust your network’s recommended resolver, you’re probably only using that resolver when you’re at home. Like I mentioned before, whenever you go to a coffee shop or hotel or use any other network, you’re probably using a different resolver. And who knows what its data collection policies are?

Beyond having your data collected and then sold without your knowledge or consent, there are even more dangerous ways the system can be exploited.

Spoofing

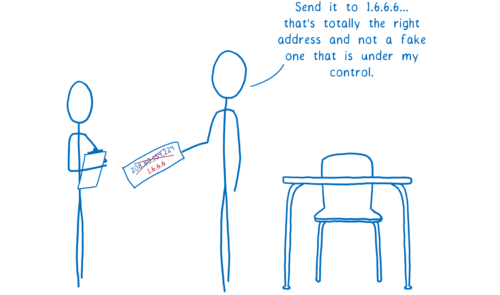

With spoofing, someone on the path between the DNS server and you changes the response. Instead of telling you the real IP address, a spoofer will give you the wrong IP address for a site. This way, they can block you from visiting the real site or send you to a scam one.

Again, this is a case where the resolver itself might act nefariously.

For example, let’s say you’re shopping for something at Megastore. You want to do a price check to see if you can get it cheaper at a competing online store, big-box.com.

But if you’re on Megastore WiFi, you’re probably using their resolver. That resolver could hijack the request to big-box.com and lie to you, saying that the site is unavailable.

How can we fix this with Trusted Recursive Resolver (TRR) and DNS over HTTPS (DoH)?

At Mozilla, we feel strongly that we have a responsibility to protect our users and their data. We’ve been working on fixing these vulnerabilities.

We are introducing two new features to fix this — Trusted Recursive Resolver (TRR) and DNS over HTTPS (DoH). Because really, there are three threats here:

- You could end up using an untrustworthy resolver that tracks your requests, or tampers with responses from DNS servers.

- On-path routers can track or tamper in the same way.

- DNS servers can track your DNS requests.

So how do we fix these?

- Avoid untrustworthy resolvers by using Trusted Recursive Resolver.

- Protect against on-path eavesdropping and tampering using DNS over HTTPS.

- Transmit as little data as possible to protect users from deanonymization.

Avoid untrustworthy resolvers by using Trusted Recursive Resolver

Networks can get away with providing untrustworthy resolvers that steal your data or spoof DNS because very few users know the risks or how to protect themselves.

Even for users who do know the risks, it’s hard for an individual user to negotiate with their ISP or other entity to ensure that their DNS data is handled responsibly.

However, we’ve spent time studying these risks… and we have negotiating power. We worked hard to find a company to work with us to protect users’ DNS data. And we found one: Cloudflare.

Cloudflare is providing a recursive resolution service with a pro-user privacy policy. They have committed to throwing away all personally identifiable data after 24 hours, and to never pass that data along to third-parties. And there will be regular audits to ensure that data is being cleared as expected.

With this, we have a resolver that we can trust to protect users’ privacy. This means Firefox can ignore the resolver that the network provides and just go straight to Cloudflare. With this trusted resolver in place, we don’t have to worry about rogue resolvers selling our users’ data or tricking our users with spoofed DNS.

Why are we picking one resolver? Cloudflare is as excited as we are about building a privacy-first DNS service. They worked with us to build a DoH resolution service that would serve our users well in a transparent way. They’ve been very open to adding user protections to the service, so we’re happy to be able to collaborate with them.

But this doesn’t mean you have to use Cloudflare. Users can configure Firefox to use whichever DoH-supporting recursive resolver they want. As more offerings crop up, we plan to make it easy to discover and switch to them.

Protect against on-path eavesdropping and tampering using DNS over HTTPS

The resolver isn’t the only threat, though. On-path routers can track and spoof DNS because they can see the contents of the DNS requests and responses. But the Internet already has technology for ensuring that on-path routers can’t eavesdrop like this. It’s the encryption that I talked about before.

By using HTTPS to exchange the DNS packets, we ensure that no one can spy on the DNS requests that our users are making.

Transmit as little data as possible to protect users from deanonymization

In addition to providing a trusted resolver which communicates using the DoH protocol, Cloudflare is working with us to make this even more secure.

Normally, a resolver would send the whole domain name to each server—to the Root DNS, the TLD name server, the second-level name server, etc. But Cloudflare will be doing something different. It will only send the part that is relevant to the DNS server it’s talking to at the moment. This is called QNAME minimization.

The resolver will also often include the first 24 bits of your IP address in the request. This helps the DNS server know where you are and pick a CDN closer to you. But this information can be used by DNS servers to link different requests together.

Instead of doing this, Cloudflare will make the request from one of their own IP addresses near the user. This provides geolocation without tying it to a particular user. In addition to this, we’re looking into how we can enable even better, very fine-grained load balancing in a privacy-sensitive way.

Doing this — removing the irrelevant parts of the domain name and not including your IP address — means that DNS servers have much less data that they can collect about you.

What isn’t fixed by TRR with DoH?

With these fixes, we’ve reduced the number of people who can see what sites you’re visiting. But this doesn’t eliminate data leaks entirely.

After you do the DNS lookup to find the IP address, you still need to connect to the web server at that address. To do this, you send an initial request. This request includes a server name indication, which says which site on the server you want to connect to. And this request is unencrypted.

That means that your ISP can still figure out which sites you’re visiting, because it’s right there in the server name indication. Plus, the routers that pass that initial request from your browser to the web server can see that info too.

However, once you’ve made that connection to the web server, then everything is encrypted. And the neat thing is that this encrypted connection can be used for any site that is hosted on that server, not just the one that you initially asked for.

This is sometimes called HTTP/2 connection coalescing, or simply connection reuse. When you open a connection to a server that supports it, that server will tell you what other sites it hosts. Then you can visit those other sites using that existing encrypted connection.

Why does this help? You don’t need to start up a new connection to visit these other sites. This means you don’t need to send that unencrypted initial request with its server name indication saying which site you’re visiting. Which means you can visit any of the other sites on the same server without revealing what sites you’re looking at to your ISP and on-path routers.

With the rise of CDNs, more and more independent sites are being served by a single server. And since you can have multiple coalesced connections open, you can be connected to multiple shared servers or CDNs at once, visiting all of the sites across the different servers without leaking data. This means this will be more and more effective as a privacy shield.

What is the status?

You can enable DNS over HTTPS in Firefox today, and we encourage you to.

We’d like to turn this on as the default for all of our users. We believe that every one of our users deserves this privacy and security, no matter if they understand DNS leaks or not.

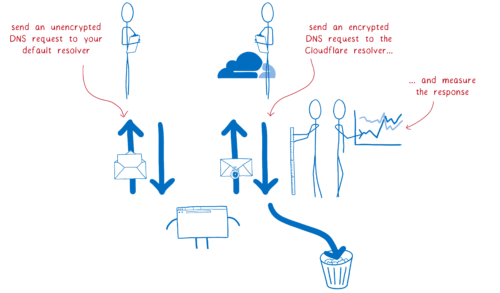

But it’s a big change and we need to test it out first. That’s why we’re conducting a study. We’re asking half of our Firefox Nightly users to help us collect data on performance.

We’ll use the default resolver, as we do now, but we’ll also send the request to Cloudflare’s DoH resolver. Then we’ll compare the two to make sure that everything is working as we expect.

For participants in the study, the Cloudflare DNS response won’t be used yet. We’re simply checking that everything works, and then throwing away the Cloudflare response.

We are thankful to have the support of our Nightly users — the people who help us test Firefox every day — and we hope that you will help us test this, too.

About Lin Clark

Lin works in Advanced Development at Mozilla, with a focus on Rust and WebAssembly.

62 comments