At Mozilla, we foresee that the future of the Web lies in its ability to connect people directly with multiple devices, without using the Internet. Many different technologies exist and are already implemented to allow peer-to-peer connections. Today is the first in a series of articles presenting these technologies. Let me introduce you to Wi-Fi Direct.

What is it about?

Wi-Fi Direct is a communication standard from the Wi-Fi Alliance that allows several devices to connect without using a local network. It has the advantage of using Wi-Fi, a fast and commonly available technology.

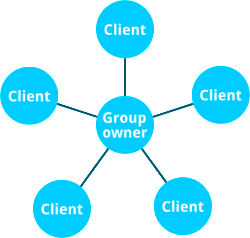

This standard allows devices to discover peers and connect to them by enabling a portable Wi-Fi access point on your device that others can connect to. In Wi-Fi Direct parlance, the access point is called a group owner. The devices connected to a group owner are called clients, or peers.

Enable Wi-Fi Direct on a Flame

In order to be usable the device driver must support Wi-Fi Direct, and that’s the case on the Flame. But before starting, the first thing to do is to enable support. Run the code in this gist with a rooted device connected to your computer.

The Wi-Fi Direct API in Firefox OS is only available to certified apps at this time. Don’t forget to request the wifi-manage permission in your manifest.webapp file. This also means that you cannot distribute such an app in the Firefox Marketplace, but you can still use it and play with the technology.

The JavaScript code in this article uses promises and some of the ES6 structures supported in the latest release of Firefox OS. Make sure you are familiar with these!

Let’s see who’s around

The Wi-Fi Direct API is accessible via the navigator.mozWifiP2pManager object.

The first thing to do: enable Wi-Fi Direct to get a list of the peers that are around. The methods to enable and get the peers are respectively setScanEnabled(true) and getPeerList() and both return promises.

navigator.mozWifiP2pManager.setScanEnabled(true)

.then(result => {

if (!result) {

throw(new Error('wifiP2pManager activation failed.'));

}

// Wi-Fi Direct is enabled! Now, let's check who's around.

return navigator.mozWifiP2pManager.getPeerList();

})

.then(peers => {

console.log(`Number of peers around: ${peers.length}!`);

});

Pass true to navigator.mozWifiP2pManager.setScanEnabled() to start Wi-Fi Direct and the promises will return true if activation was successful. Use this to check whether your device supports Wi-Fi Direct or not.

The promise returned by navigator.mozWifiP2pManager.getPeerList() will return an array of objects representing the peers located around you with Wi-Fi Direct enabled:

{

name: "Guillaume's Flame",

connectionStatus: "disconnected",

address: "02:0a:f5:f7:38:44", // MAC address of the device

isGroupOwner: false

}

The peer name can be set using navigator.mozWifiP2pManager.setDeviceName(`Guillaume's Flame`). It is a string that allows a human to identify a device.

As you can guess, the connectionStatus property tells us whether the device is connected or not. It has 4 possible values:

- ‘disconnected’

- ‘connecting’

- ‘connected’

- ‘disconnecting’

You can listen to the peerinfoupdate event fired by navigator.mozWifiP2pManager to know when any peer status changes (new peer appears or disappears ; a peer connection status changes). You need then to call getPeerList() to get the update.

Knock knock. Who’s there?

Now that we know the devices located around you, let’s connect with them. We’re going to use navigator.mozWifiP2pManager.connect(address, wps, intent). The 3 parameters stand for:

- The MAC address of the device

- The WPS method (e.g. ‘pbc’)

- A value for intent from 0 to 15

The MAC address is given in the peer object retrieved with getPeerList().

The WPS method can be safely ignored for now but keep an eye on MDN for more on this.

For initial connections, the value of intent will decide who will be the group owner of the Wi-Fi Direct network. The higher the value, the more likely it is that the device issuing the connection is the group owner.

// Given `peer`, a peer object.

navigator.mozWifiP2pManager.connect(peer.address, 'pbc', 1)

.then(result => {

if (!result) {

throw(new Error(`Cannot request a connection with ${peer.name}.`));

}

// The connect request was successfully issued.

});

At this stage, you’re still not connected to the peer. The value returned will tell you whether the connection could be initiated or not.

To know the status of your connection, you need to listen to an event.

Breaking the ice

The Wi-Fi Direct object emits different types of events. When another device gets connected the statuschange event is fired.

The details of the connection are available in navigator.mozWifiP2pManager.groupOwner. Use the information provided by the following properties:

isLocal: whether the device is a group owner or not.ipAddress: the IP address of the group owner.

More properties are also exposed, but the ones above are enough to build a basic application.

statuschange is also triggered when the other peer is disconnected using navigator.mozWifiP2pManager.disconnect(address).

Say hello

Wi-Fi Direct is merely a connection protocol, it’s now up to you to decide how to communicate. Once connected, you get the IP address of the group owner. This can be used with fxos-web-server, a web server running on your device to request information. The group owner will then act as a server.

You can also use p2p-helper.js, a convenient helper library developed by Justin D’Arcangelo to abstract away the complexity of the Wi-Fi Direct API and build an app with ease.

I recommend you have a look at the following example apps:

- Firedrop, a sample app to share media files between devices.

- Wi-Fi Columns, a game working across multiple devices. See the demo below.

Now, it’s your turn to create mind-blowing apps where multiple devices can interact together without cellular data or Internet connection!

About Guillaume Cedric Marty

Guillaume has been working in the web industry for more than a decade. He's passionate about web technologies and contributes regularly to open source projects, which he writes about on his technical blog. He's also fascinated by video games, animation, and, as a Japanese speaker, foreign languages.

8 comments