When styling a web site with CSS you might have realised that an inch on a screen is not an actual inch, and a pixel is not necessarily an actual pixel. Have you ever figured out how to represent the speed of light in CSS pixels? In this post, we will explore the definition of CSS length units starting by understanding some of the physical units with the same name, in the style of C.G.P. Grey[1].

The industrial inch (in)

People who live in places where the inch is a common measure are already familiar with the physical unit. For the rest of us living in places using the metric system, since 1933, the “industrial inch” has been defined as mathematical equivalent of 2.54 centimeters, or 0.0254 metres.

The device pixel

Computer screens display things in pixels. The single physical “light blob” on the display, capable of displaying the full color independent of it’s neighbour is called a pixel (picture element). In this post, we refer to the physical pixel on the screen as “device pixel” (not to be confused with CSS pixel which will be explained later on).

Display pixel density, dots per inch (DPI), or pixels per inch (ppi)

The physical dimension of a device pixel on a specific device can be derived from the display pixel density given by the device manufacturer, usually in dots per inch (DPI), or pixels per inch (PPI). Both units are essentially talking about the same thing when they refer to a screen display, where DPI is the commonly-used-but-incorrect unit and PPI is the more-accurate-but-no-one-cares one. The physical dimension of a device pixel is simply the inverse number of it’s DPI.

The MacBook Air (2011) I am currently using comes with a 125 DPI display, so

(width or height of one device pixel) = 1/125 inch = 0.008 inch = 0.02032 cm

Obviously this is a number too small to be printed on the specification, so the DPI stays.

The CSS pixel (px)

The dimension of a CSS pixel can be roughly regarded as a size to be seen comfortably by the naked human eye, not too small so you’d have to squint, and not big enough for you to see pixelation. Instead of consulting your ophthalmologist on the definition of “seen comfortably”, the W3C CSS specification gives us a recommend reference:

The reference pixel is the visual angle of one pixel on a device with a pixel density of 96 DPI and a distance from the reader of an arm’s length.

The proper dimension of a CSS pixel is actually dependent on the distance between you and the display. With the exception of Google Glass (which mounts on your head), people usually find their own unique comfortable distance, dependent on their eyesight, for a particular device. Given the fact we have no way to tell whether the user is visually impaired, what concerns us is simply typical viewing distance for the given device form factor — e.g., a mobile phone is usually held closer, and a laptop is usually used on a desk or a lap. Thus, the “viewing distance” of mobile phones is shorter than the one of laptops, or desktop computers.

The viewing distance

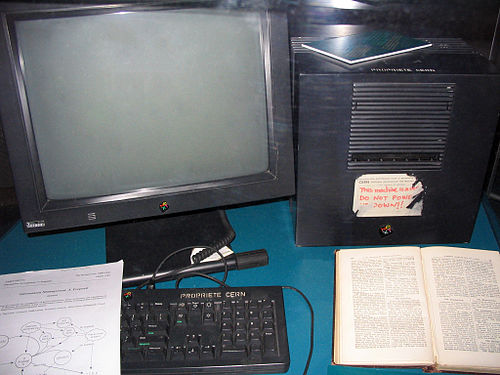

As previously mentioned, the viewing distance varies from person to person and from device to device, which is why we must categorise devices into form factors. The recommended reference viewing distance (“an arm’s length”) and the reference pixel density (“96 DPI”) is actually historical; it is a testimony of the way people during the late-20th century usually accessed the web:

The first computer that runs the web. From Wikipedia: WWW.

For day-to-day devices of the 21st century, we have different reference recommendations:

|

Baseline pixel density |

Width/height of one CSS pixel |

Viewing distance |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

A 20th century PC with CRT display |

96 DPI |

~0.2646 mm (1/96in) |

28 in (71.12cm) |

|

Modern laptop with LCD[2] |

125 DPI |

0.2032 mm (1/125in) |

21.5 in (54.61cm) |

|

Smartphones/Tablets[3] |

160 DPI |

~0.159mm (1/160 in) |

16.8in (42.672cm) |

From this table, it’s pretty easy to see that as the pixel density increases and size of a CSS pixel gets smaller, muggles like you and me usually need to hold the device closer to comfortably see what’s on the device screen.

With that, we established a basic fact in the world of CSS: a CSS pixel will be displayed in different physical dimensions but it will always be displayed in the correct size in which the viewer will find comfortable. By leveraging the principle, we can safely set the basic dimensions (e.g. base font size) to a fixed pixel size, independent of device form factors.

CSS inch (in)

On a computer screen, a CSS inch has nothing to do with the physical inch. Instead, it is being redefined to be exactly equal to 96 CSS pixels. This has resulted in an awkward situation, where you can never reliably draw an accurate ruler on the screen with basic CSS units[4]. Yet this gives us what’s intended: elements sized in CSS units will always be displayed across devices in a way where the user will feel comfortable.

As a side note, if the user prints out the page on a piece of paper, browsers will map the CSS inch to the physical inch. You can reliably draw an accurate ruler with CSS and print it out. (make sure you’d turn off “scale to fit” in the printer settings!)

Device pixel ratio (DPPX)

As we step into the future (where is my flying car?), many of the smartphones nowadays are shipped with high-density displays. In order to make sure that CSS pixels are sized consistently across every device that accesses the web (i.e. everything with a screen and network connection), device manufacturers had to map multiple device pixels to one CSS pixel to make up for it’s relative bigger physical size. The ratio of the dimension of CSS pixel relative to device pixels is the device pixel ratio (DPPX).

Let’s take iPhone 4 as the most famous example. It comes with a 326 DPI display. According to our table above, as a smartphone, it’s typical viewing distance is 16.8 inches and it’s baseline pixel density is 160 DPI. To create one CSS pixel, Apple chose to set the device pixel ratio to 2, which effectively makes iOS Safari display web pages in the same way as it would on a 163 DPI phone.

Before we move on, take a look back on the numbers above. We can actually do better by not setting device pixel ratio to 2 but to 326/160 = 2.0375, and make a CSS pixel exactly the same compared to the reference dimensions. Unfortunately, such ratio will result in an unintended consequence: as each CSS pixel is not being displayed by whole device pixels, the browser would have to make some efforts to anti-alias all the bitmap images, borders, etc. since almost always they are defined as whole CSS pixels. It’s hard for browsers to utilize 2.0375 device pixels to draw your 1 CSS pixel-wide border: it’s way more easier to do it if the ratio is simply 2.

Incidentally, 163 DPI happens to be the pixel density of the previous generation of the iPhone, so the web will work the same way without having developers to do any special “upgrades” to their websites.

Device manufacturers usually choose 1.5, or 2, or other whole numbers as the DPPX value. Occasionally, some devices decided not to play nice and shipped with something like 1.325 DPPX; as web developers, we should probably ignore those devices.

Firefox OS, initially being a mobile phone operating system, implemented DPPX calculation in this way. The actual DPPX will be determined by the manufacturer of each shipping device.

CSS point (pt)

Point is a commonly used unit that came from the typography industry, as the unit for metal typesetting. As the world gradually moved from letterpress printing to desktop publishing, a “PostScript point” was then redefined as 1/72 inches. CSS follows the same convention and mapped 1 CSS point to 1/72 CSS inches, and 96/72 CSS pixels.

You can easily see that just like a CSS inch, on a device display, CSS point has little to do with the traditional unit. Its size only matches it’s desktop publishing counterpart when we actually print out the web page.

CSS pica (pc), CSS centimeter (cm), CSS millimeter (mm)

Just like CSS inch, while their relative relationships are kept, their basic size on the screen have been redefined by CSS pixel, instead of the standard SI unit (metre), which is defined by the speed of light, a universal constant.

We could literally redefine the speed of light in CSS; it is 1,133,073,857,007.87 CSS pixels per second[5] — relativity in CSS makes light travel a bit slower on devices with smaller form factors than traditional PCs, from our perspective, looking into the screen from the real world.

The viewport meta tag

Though the smartphone is handy in the palm of your hand and its guaranteed that CSS pixels will be displayed in a size comfortable to users, a device capable of showing only a part of a fixed-width desktop website is not going to be very useful. It would be equally not useful if the phone violated the CSS unit rules and pretended it to be something else.

The introduction of the viewport meta tag brought the best of both worlds to mobile devices by giving the control of page scaling to both users and web developers. You could design a mobile layout, and opt out of viewport scaling, or, you could leave your website made for desktop browsers as-is and have the mobile browser scale down the page for you and the user. As always, detailed descriptions and usage can be found on Mozilla Developer Network.

Conclusion

Browser vendors, while being in competition, recognize the effort of maintaining the stability of the Web platform and coordinate their feature sets through a standard organization. Features and APIs exposed will be carefully tested for their usefulness across all scenarios, before declaring their suitability as a standard. The definition of CSS pixel has one of those since the beginning. New features introduced must maintain backward-compatibility instead of changing the old behavior[6], so many of them (device pixels, viewport meta tag, etc.) are being introduced as extra layers of complexity. Old web pages that use standardized features, thus have a built-in “forward-compatibility”.

With that in mind, Mozilla, together with our partners, nurture and defend the Open Web — the unique platform that we all cherish.

[1] Well, not actually, cause we are not going to make a video about it. I won’t mind if C.G.P. Grey actually made a video about this!

[2] Appears to be common values for laptops[citation needed].

[3] The typical value is documented here as a “mdpi” Android device.

[4] With one exception: the non-standard CSS unit mozmm gives you the ability to do so provided that Firefox knows the pixel density it runs on. This is out of scope of our topic there.

[5] 299,792,458 metres per second ÷ 0.0254 meters per inch x 96 pixels per inch

[6] There was a brief period of time where people tried to come up with an entirely new standard that breaks backward compatibility (*cough* xHTML *cough*), but that’s a story for another time.

About Tim Chien

Timothy Guan-tin Chien, a.k.a. “timdream”, is an engineering manager and front-end web developer working on "Gaia", the mobile UI for Firefox OS. He enjoy writing code, giving talks, and try to blog regularly at blog.timc.idv.tw.

About Robert Nyman [Editor emeritus]

Technical Evangelist & Editor of Mozilla Hacks. Gives talks & blogs about HTML5, JavaScript & the Open Web. Robert is a strong believer in HTML5 and the Open Web and has been working since 1999 with Front End development for the web - in Sweden and in New York City. He regularly also blogs at http://robertnyman.com and loves to travel and meet people.

26 comments