The audio team is made up of a group Mozilla volunteers who developed the Audio API and, most recently, a new generation of WebGL demos. This is the story of the development of the No Comply demo.

In the fall, after finishing Flight of the Navigator, our team of audio and WebGL hackers was looking for a new challenge. We’d finished the new Audio API in time for Firefox 4, and were each maintaining various open web libraries, exploiting the new features of HTML5, Audio, JavaScript, and WebGL. We wanted to take another shot at testing the limits of Firefox 4 – then, still in beta.

Seth Bindernagel had the answer. He’d been in contact with a DJ and producer friend named Kraddy, who had just finished an amazing new album. “What if we tried to do something with his sound?” The idea was too good to pass up, and with Kraddy’s support, we dove into the tracks and started imagining what these songs might look like, when interpreted through the medium of the web.

«The web that Firefox 4 makes possible is a web ready for artists, developers, filmmakers, and musicians alike»

Kraddy’s music was easy to demo because of its complex nature, with plenty of emphatic transitions and cue points–this music wants to be visualized! The music for No Comply also provided a dark and introspective sound on which to build a narrative. On his blog, Kraddy had already written about how he understood the album’s meaning:

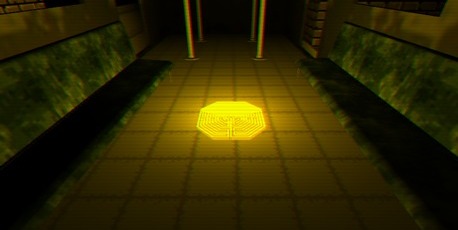

This EP is about Theseus’ decision to be a hero and his decent into the Labyrinth to kill the Minotaur. In a broader sense the EP is about the battle we all face when we challenge ourselves as people. We must enter the Labyrinth of our minds and at the center we find our greatest fears. To defeat those fears we must kill a part of ourselves. And in killing a part of ourselves we create the potential to grow into a more developed person.

Kraddy’s vision informed our early outlines and storyboards. We knew that we wanted to play on the story of the Minotaur and the Maze, and the idea of facing down ones’ own fears. Together we came up with the idea of re-telling the story using a mixture of real-life video and 8-bit video game styling. Because the album was deeply personal to Kraddy, we decided to feature him in the demo. Kraddy agreed to be filmed, and Brett Gaylor used the footage to create the opening and closing video sequences. We also used Kraddy as the inspiration for the demo’s main video game character.

The launch of Firefox 4 brings a lot to the web, not least WebGL. As the web shifts from a 2D-only to a 2D and 3D space, we wanted to explore the intersection of these two familiar graphical paradigms. Rather than picking just one, we chose to create a hybrid, dream world, composed of 3D and 2D elements. Many people will recognize in our 2D characters and graphics an homage to much earlier video games, like Double Dragon. We wanted to celebrate the fact that these two paradigms can now exist together in a simple web page–everything we do in the demo is one web page, whether audio, video, 2D, 3D, or text.

Like the Flight of the Navigator(FOTN) demo before it, we chose the CubicVR.js engine to drive all the 3D graphics. Over the months leading up to the demo, Charles J. Cliffe had begun the painstaking process of porting features from his C++ engine over to JavaScript. The simple environment of WebGL and JavaScript allowed for features that even his C++ version did not yet posses to be quickly prototyped. Many bottlenecks had to be overcome during iterations of the demo, as we wanted to push the limits further than before. The biggest hurdle was visibility and lighting. Luckily, Bobby Richter came to the rescue. Using his experience with Octrees, he was able to work with Charles to produce a visibility and lighting pipeline which provides impressive performance for the task. In contrast, FOTN has no visibility system and was shaded by a single global directional light and ambient surface textures (for window lights, etc.) to simulate the rest. In No Comply we were able to push the limits with high poly counts and many overlapping point lights and were still able to reach the framerate cap.

Creating a 3D world like the one in this demo requires a lot of original content creation, which in turn requires some sophisticated tools. Instead of developing our own, and in the open-nature of our group, we decided to use existing technology like Blender. The community that develops Blender and creates content with it is rich and diverse, and because it’s an open tool, we could add the features we needed when they weren’t already present.

Our preference for open technologies also meant that the COLLADA scene format was an obvious choice. Unfortunately, as of version 2.49, Blender exports an Autodesk-inspired format of COLLADA, which isn’t quite up to the official standard, missing many important bits of information. Fixing this directly in Blender (with a little bit of Python hacking) let CubicVR stay standards-compliant, and let us milk Blender for all of the scene information we could think of using.

The demo’s 3D modelling, while important, comprises perhaps only half of No Comply’s original content. An incredible undertaking on the part of Omar Noory provided the textures for the rich environment through which Kraddy rumbles and tumbles. Frequently, spontaneous requests for “an 8 bit trash can,” “a cool sign with our names on it,” or, “some beefy bad lookin’ dudes” were answered almost instantly by Omar’s gracious and masterful digital pen. You may have recognized Omar’s name from his claim to meme-fame with “Haters Gonna Hate”.

Adding the perfect amount of flare to the graphics pipeline is Al MacDonald’s Burst animation engine. Al not only wrote our sprite animation engine, but also the web-based toolset we used to create the animations. The 8-bit Kraddy and all of No Comply’s 8-bit baddies are driven by animation paths prepared with Burst, and engineered with a set of tools that work right inside the browser.

In addition to cutting edge graphics with WebGL and <canvas>, we also wanted to explore how far we could push the new Firefox 4 Audio API we’d developed. The Audio Data API allows us to do many new things with the HTML5 <audio> and <video> tags, such as outputting generated audio and revealing realtime audio data to JavaScript. Libraries like Corban Brook’s DSP.js and and Charles’ BeatDetektor.js were used to analyze the audio in realtime and trigger various effects and animation sequences. Tracks of audio triggers were also recorded for tighter sequencing of key elements in the song we wanted to emphasize. One of the really new techniques we played with a lot in the demo was controlling GLSL shaders and lighting directly with audio, punching in and out with every beat and clap. Unlike most treatments of audio on the web, in this demo the song isn’t a background element, but is woven into the fabric of all the visuals and effects.

Getting a demo of this scale to work in the browser means figuring out how to make every bit of it work fast, and keep framerates high. Everything we do in the demo, from loading and parsing massive COLLADA models, to controlling 3D scene graphs, to analyzing real-time audio data, is done with JavaScript. We think it’s important to point this out because so many people begin with the assumption that JavaScript isn’t fast enough for the kind of work we’re presenting. The truth is that modern JavaScript, like that in Firefox 4, has been so heavily optimized that we all need to rethink what is and isn’t possible on the web.

We’ve taken advantage of a bunch of Firefox 4’s new performance features, as well as new HTML5 goodies, in order to make this all possible. For example Web Workers let us move heavy resource parsing off the main thread, freeing it for audio analysis and 3D effects. While a large portion of each second is consumed by simply pushing information to the video card, it isn’t necessary for the browser to wait for that to happen. In the background, we can use other threads to load and parse data, so that it’s ready to draw when the main thread needs it. Of course, a host of problems arise immediately whenever concurrency is involved, but we managed to draw a large performance and overall stability increase by utilizing Web Workers.

Another performance trick was using JavaScript Typed Arrays, which give us a tremendous speed boost when working with audio and pixel data. When you’re analyzing slices of audio data hundreds of bytes wide as fast as possible, your Fourier Transform code needs to be blazingly quick. Thanks to Corban’s highly optimized dsp.js library, this was hardly on our minds.

Next, we spent a lot of time optimizing our JavaScript so that it could take advantage of Firefox’s Tracing and Method JIT. Writing code that can be easily byte-compiled by the browser makes sure that anything we write runs as fast as possible. This is a fairly new and surprising concept, especially to those who remember the JavaScript of yesterday.

Part of what appealed to us about writing this demo was that it let those of us who are browser developers, and those of us who are web developers, work together on a single project. Most of the technology showcased in this demo was made on bleeding edge Firefox nightlies and our development process involved lots of feedback about performance or stability issues in the browser. Dave Humphrey focused on the internals of the Audio API, instrumenting and profiling our JavaScript, and helped us work closely with Mozilla’s JavaScript, graphics, and WebGL engineers. People like Benoit Jacob and Boris Zbarsky, among others, were indispensable as we worked to fix various bottlenecks. Part of what makes Mozilla such a successful project is that their engineers are not locked away, unable to work with web developers. Having engineers at our beck and call was essential to our success with such a demanding schedule, and we were proud to be able to help Mozilla test and improve Firefox 4 along the way.

Beyond the technical aspects of the demo, it also points to the spirit of how these technologies are meant to be used. We worked as a distributed team during evenings and on weekends, to plan and code and create everything, from the tools we needed to the graphical resources to the demo’s final code. Some of our team are browser developers, some web and audio hackers, others are graphic designers or filmmakers, still others storytellers and writers–everyone had a place around the table, and a role to play. We think this is part of what makes the web such a powerful platform for creative and collaborative work: there isn’t one right way to be, no single technology you need to know, and the techniques and tools are democratized and open to anyone willing to pick them up. The web that Firefox 4 makes possible is a web ready for artists, developers, filmmakers, and musicians alike.

About Paul Rouget

Paul is a Firefox developer.

13 comments